Fall River Skeleton in Armor

From Kook Science

The Skeleton in Armor was a human skeleton dressed in a bronze breastplate and belt and buried with artifacts, including metal arrowheads, that was exhumed from a digging at Fall River, Bristol Co., Massachusetts during 1831, and subsequently destroyed during the Great Fire of 1843 while on display at the Fall River Athenaeum. Prior to their destruction, the skeletal remains and burial artifacts were the object of speculation as to their origin: many supposed they had belonged to local aboriginal peoples, while others advanced hypotheses that they were Phoenician or Norse, the latter claim being notably advanced as a poetic basis for Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's ballad The Skeleton in Armor.

Reading

Stark (1837)

- Stark, John (July 1837), Hawthorne, Nathaniel, ed., "Antiquities of North America", American Magazine of Useful and Entertaining Knowledge 3: 434-435, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=osu.32435073186454&view=1up&seq=447&skin=2021

[...] a description of what we consider the most interesting relic of antiquity ever discovered in North America — the remains of a human body, armed with a breast-plate, a species of mail, and arrows of brass; which remains we suppose to have belonged either to one of the race who inhabited this country for a time anterior to the so called Aborigines, and afterwards settled in Mexico or Guatamala, or to one of the crew of some Phœnician vessel, that, blown out of her course, thus discovered the western world long before the Christian era.

These remains were found in the town of Fall River, in Bristol County, Mass., about eighteen months since.

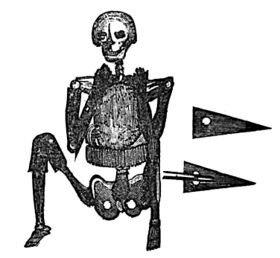

In digging down a hill near the village, a large mass of earth slid off, leaving in the bank, and partially uncovered, a human skull, which on examination was found to belong to a body buried in a sitting posture; the head being about one foot below what had been for many years the surface of the ground. The surrounding earth was carefully removed, and the body found to be enwrapped in a covering of coarse bark of a dark color. Within this envelope were found the remains of another of coarse cloth, made of fine bark, and about the texture of a Manilla coffee-bag. On the breast was a plate of brass, thirteen inches long, six broad at the upper end and five at the lower. This plate appears to have been cast, and is from one-eighth to three thirty-seconds of an inch in thickness. It is so much corroded that whether or not anything was ever engraved upon it has not yet been ascertained. It is oval in form, the edges being irregular, apparently made so by corrosion.

Below the breastplate, and entirely encircling the body, was a belt composed of brass tubes,each four and a half inches in length and three-sixteenths of an inch in diameter, arranged longitudinally and close together; the length of the tube being the width of the belt. The tubes are of thin brass, cast upon hollow reeds, and were fastened together by pieces of sinew. This belt was so placed as to protect the lower parts of the body below the breastplate. The arrows are of brass, thin, flat, and triangular in shape, with a round hole cut through near the base. The shaft was fastened to the head by inserting the latter in an opening at the end of the wood, and then tying it with a sinew through the round hole,— a mode of constructing the weapon never practiced by the Indians, not even with their arrows of thin shell. Parts of the shaft still remain on some of them. When first discovered the arrows were in a sort of quiver of bark, which fell in pieces when exposed to the air.

The following sketch will give our reads an idea of the posture of the figure and the position of the armor. When the remains were discovered the arms were brought rather closer to the body than in the engraving. The arrows were near the right knee.

The skull is much decayed, but the teeth are sound and apparently of a young man. The pelvis is much decayed and the smaller bones of the lower extremities are gone.

The integuments of the right knee, for four or five inches above and below, are in good preservation, apparently the size and shape of life, although quite black.

Considerable flesh is still preserved on the hands and arms, but more on the shoulders and elbows. On the back under the belt, and for two inches above and below, the skin and flesh are in good preservation, and have the appearance of being tanned. The chest is much compressed, but the upper viscera are probably entire. The arms are bent up, not crossed; so that the hands turned inwards touch the shoulders. The stature is about five and a half feet. Much of the exterior envelope was decayed, and the inner one appeared to be preserved only where it had been in contact with the brass.

The preservation of this body may be the result of some embalming process; and this hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that the skin has the appearance of having been tanned; or it may be the accidental result of the action of the salts of the brass during oxidation; and this latter hypothesis is supported by the fact that the skin and flesh have been preserved only where they have been in contact with or quite near the brass; or we may account for the preservation of the whole by supposing the presence of saltpetre in the soil at the time of the deposit. In either way, the preservation of the remains is fully accounted for, and upon known chemical principles.

That the body was not one of the Indians we think needs no argument. We have seen some of the drawings taken from the sculptures found at Palenqué, and in those the figures are represented with the breast-plates, although smaller than the plate found at Fall River. On the figures at Palenqué the bracelets and anklets seem to be of a manufacture precisely similar to the belt of tubes just described. These figures also have helmets precisely answering the description of Hector in Homer.

If the body found at Fall River be one of the Asiatic race, who transiently settled in Central America, and afterwards went to Mexico and founded those cities, in exploring the ruins of which such astonishing discoveries have recently been made; then we may well suppose also that it is one of the race whose exploits have, although without a date and almost without a certain name, been immortalized by the Father of Poetry; and who, probably in still earlier times, constructed the Clocæ under ancient Rome, which have been absurdly enough ascribed to one of the Tarquins, in whose times the whole population of Rome would have been insufficient for a work, that would, moreover, have been useless when finished. Of this Great Race, who founded cities and empires in their eastward march, and are finally lost in South America, the Romans seem to have had a glimmering tradition in the story of Evander.

But we rather incline to the belief that the remains found at Fall River belonged to the crew of a Phœnician vessel.

The spot where they were found is on the sea-coast, and in the immediate neighborhood of 'Dighton Rock,' famed for its hieroglyphic inscriptions, of which no sufficient explanation has yet been given: and near which rock brazen vessels have been found. If this latter hypothesis be adopted, a part of it is that these mariners — the unwilling and unfortunate discoverers of a new world — lived some time after they landed; and having written their names, perhaps their epitaphs, upon the rock at Dighton, died, and were buried by the natives.

Gibbs (1853)

- Gibbs, George (1853), "Skeleton in Armor", in Schoolcraft, Henry R., Information, Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States: Collected and Prepared Under the Direction of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Per Act of Congress of March 8d, 1847, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Company, p. 127-129, https://archive.org/details/historicalstati00scho/page/126/mode/2up

Archaeological Evidences That the Continent Had Been Visited by People Having Letters, Prior to the Era of Columbus.

5. Skeleton in Armor.[The following description of certain human skeletons, supposed to be in armor, found at Fall River, or Troy, in Massachusetts, is from the pen of George Gibbs, Esq. It is drawn with that writer's usual caution and archaeological acumen.]

Some years since, accounts were published in the Rhode Island newspapers and extensively copied elsewhere, stating that a skeleton in armor had been discovered near Fall River, on the Rhode Island line. A full description was also published in one of our periodicals (it is believed the American Monthly Magazine), and thence copied into Stone's Life of Brant (appx. 19, Vol. 2), in which, from the character of the armor, it was conjectured to be of Carthaginian origin — the remains of some ship-wrecked adventurer. Other theories have been more recently started, in consequence of the discoveries of the Northern Society of Danish Antiquaries, and their interpretations of the hieroglyphic figures on the rocks at Dighton and elsewhere, which attribute the remains to one of the fellow-voyagers of Thorfin. These speculations, however, seem to have been made without any critical examination of the bones themselves, or the metallic implements found with them. The discovery, during the last summer (1839), of other bodies, also with copper ornaments or arms, led to a more particular inquiry, and my informant, who was then at Newport, proceeded to Fall River for the purpose of inspecting them. The following description was prepared by him from notes taken on the spot, and is to be relied on as strictly accurate. It may serve to correct a false impression in a matter of some historical importance, and for that reason only is deemed worthy of attention.

"The Skeleton found some years ago is now in the Athenæum at Troy. As many of the ligaments had decayed, it has been put together with wires, and in a sitting posture. The bones of the feet are wanting, but the rest of it is nearly entire. The skull is of ordinary size, the forehead low, beginning to retreat at not more than an inch from the nose, the head conical, and larger behind the ears than in front. Some of the facial bones are decayed, but the lower jaw is entire, and the teeth in good preservation. The arms are covered with flesh and pressed against the breast, with the hands almost touching the collar-bone. This position, however, may have been given to it after being dug up. The hands and arms are small, and the body apparently that of a person below the middle size. The flesh on the breast and some of the upper ribs is also remaining: it is of a black color, stringy, and much shrunk. The leg bones correspond in size and length with the arms. A piece of copper plate, rather thicker than sheathing copper, was found with this skeleton, and has been hung round the neck. This, however, does not seem to be its original position, as there were no marks on the breast of the green carbonate with which parts of the copper was covered. This plate was in shape like a carpenter’s saw, but without serrated edges; it was ten inches in width, six or seven inches wide at top, and four at the bottom ; the lower part broken, so that it had probably been longer than at present. The edges were smooth, and a hole was pierced in the top by which it appears to have been suspended to the body with a thong. Several arrow-heads of copper were also found, about an inch and a half long by an inch broad at the base, and having a round hole in the centre to fasten them to the shaft. They were flat, and of the same thickness with the plate above mentioned, and quite sharp, the sides concave, the base square and not barbed. Pieces of the shaft were also found.

The most remarkable thing about this skeleton, however, was a belt, composed of parallel copper tubes, about an hundred in number, four inches in length, and of the thickness of a common drawing-pencil.

These tubes were thin, and exterior to others of wood, through each of which a leather thong was passed, and tied at each end to a long one passing round the body.

These thongs were preserved, as well as the wooden tubes ; the copper was much decayed, and in some places gone. This belt was fastened under the left arm, by tying the ends of the long strings together, and passed round the breast and back a little below the shoulder-blades. Nothing else was found, but a piece of coarse cloth or matting, of the thickness of sail-cloth, a few inches square. It is to be observed that the flesh appeared to have been preserved wherever any of the copper touched it.

I could not learn the place where this body was found, or its position.

With respect to the bodies found this summer, I saw the man who dug them up. They were found in ploughing down a hill, in order to open a road, about three or four feet under ground, some two or three hundred yards from the water, and nearly opposite Mount Hope.

There appeared to have been at least three bodies interred here, but they were entirely broken up by the plough; one skull only, which resembled in shape the one above described, being found whole. The flesh on one of the thigh-bones was entire, and similar in color and substance to that in the first skeleton, and like that. It bore the marks of copper rust. Three or four plates of copper like that first found were discovered, one having a leather thong through the hole in the top. Arrow-heads of copper were also found, and parts of the shafts. One arrow-head was fastened on by a piece of cord like a fishing-line well twisted, passing through the hole, and wound round the shaft. There were also some more matting, a bunch of short, red, curled hair, and one of black hair, but neither resembling that of a man, and a curved bar of iron about fourteen inches long, much rusted, not sharpened, but smaller at one end than at the other. It did not appear to have been used as a weapon. These were all the remains discovered.”

Such are the famous Fall River skeletons. But little argument is necessary, to show that they must have been North American Indians. The state of preservation of the flesh and bones, proves that they could not have been of very ancient date; the piece of the skull now exhibited being perfectly sound, and with the serrated edge of the suture.

The conical formation of the skull peculiar to the Indian, seems also conclusive. The character of the metallic implements found with them, is not such as to warrant any other supposition.

Both Rome and Phoenicia were well acquainted with the elaborate working of iron and brass; these were apparently mere sheet-copper, rudely cut into simple form; neither the belt nor plates were fit for defensive armor. And lastly, the use of copper for arrow-heads among the Indians at the arrival of the Puritans, is well authenticated. Mention is made of them by Mourt, in his Journal of Plymouth Plantation, in 1620, printed in the eighth volume of Massachusetts Historical Collections, pages 219-20; in Higgeson's New England Plantation, first volume of Massachusetts Historical Collections, page 123, and in various other places. They are also found in many of the tumuli of the West. Those of the New England Indians may have been obtained, from the people of French Acadie, who traded with them long before the Plymouth settlement.

From these circumstances it appears that the skeletons at Fall River were those of Indians who may possibly have lived during the time of Philip’s wars, or a few years earlier, but that they are only those of Indians.

Longfellow (1876)

From an edition copyrighted 1876, though the ballad itself was originally written around 1841, being originally published in Lewis Gaylord Clark's The Knickerbocker.

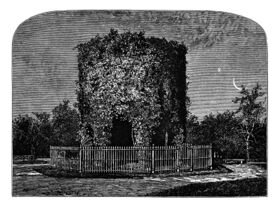

THIS Ballad was suggested to me while riding on the seashore at Newport. A year or two previous a skeleton had been dug up at Fall River, clad in broken and corroded armor; and the idea occurred to me of connecting it with the Round Tower at Newport, generally known hitherto as the Old Wind-Mill, though now claimed by the Danes as a work of their early ancestors. Professor Rafn, in the Mémoires de la Socéité Royale des Antiquaires du Nord, for 1838-1839, says:—

"There is no mistaking in this instance the style in which the more ancient stone edifices of the North were constructed,— the style which belongs to the Roman or ante-Gothic architecture, and which, especially after the time of Charlemagne, diffused itself from Italy over the whole of the West and North of Europe, where it continued to predominate until the close of the twelfth century,— that style, which some authors have, from one of its most striking characteristics, called the round-arch style, the same which in England is denominated Saxon and sometimes Norman architecture.

"On the ancient structure in Newport there are no ornaments remaining, which might possibly have served to guide us in assigning the probable date of its erection. That no vestige whatever is found of the pointed arch, nor any approximation to it, is indicative of an earlier rather than of a later period. From such characteristics as remain, however, we can scarcely form any other inference than one, in which I am persuaded that all, who are familiar with Old-Northern architecture, will concur, THAT THIS BUILDING WAS ERECTED AT A PERIOD DECIDEDLY NOT LATER THAN THE 12TH CENTURY. This remark applies, of course, to the original building only, and not to the alterations that it subsequently received, for there are several such alterations in the upper part of the building which cannot be mistaken, and which were most likely occasioned by its being adapted in modern times to various uses; for example, as the substructure of a windmill, and latterly as a hay magazine. To the same times may be referred the windows, the fireplace, and the apertures made above the columns. That this building could not have been erected for a wind-mill is what an architect will easily discern."

I will not enter into a discussion of the point. It is sufficiently well established for the purposes of a ballad; though doubtless many an honest citizen of Newport, who has passed his days within sight of the Round Tower, will be ready to exclaim with Sancho, "God bless me! did I not warn you to have a care of what you were doing, for that it was nothing but a wind-mill; and nobody could mistake it, but one who had the like in his head."

Speak! speak! thou fearful guest,

Who, with thy hollow breast

Still in rude armor drest,

Comest to daunt me!

Wrapt not in Eastern balms,

But with thy fleshless palms

Stretched, as if asking alms,

Why dost thou haunt me?"

Then, from those cavernous eyes

Pale flashes seemed to rise,

As when the Northern skies

Gleam in December;

And, like the water's flow

Under December's snow,

Came a dull voice of woe

From the heart's chamber.

"I was a Viking old!

My deeds, though manifold,

No Skald in song has told,

No Saga taught thee!

Take heed, that in thy verse

Thou dost the tale rehearse,

Else dread a dead man's curse

For this I sought thee.

"Far in the Northern Land,

By the wild Baltic's strand,

I, with my childish hand,

Tamed the ger-falcon;

And, with my skates fast-bound,

Skimmed the half-frozen Sound,

That the poor whimpering hound

Trembled to walk on.

"Oft to his frozen lair

Tracked I the grisly bear,

While from my path the hare

Fled like a shadow;

Oft through the forest dark

Followed the were-wolf's bark,

Until the soaring lark

Sang from the meadow.

"But when I older grew,

Joining a corsair's crew,

O'er the dark sea I flew

With the marauders.

Wild was the life we led;

Many the souls that sped,

Many the hearts that bled

By our stern orders.

"Many a wassail-bout

Wore the long Winter out;

Often our midnight shout

Set the cocks crowing,

As we the Berserk's tale

Measured in cups of ale,

Draining the oaken pail,

Filled to o'erflowing.

"Once as I told in glee

Tales of the stormy sea,

Soft eyes did gaze on me,

Burning yet tender;

And as the white stars shine

On the dark Norway pine,

On that dark heart of mine

Fell their soft splendor.

"I wooed the blue-eyed maid,

Yielding, yet half afraid,

And in the forest's shade

Our vows were plighted.

Under its loosened vest

Fluttered her little breast,

Like birds within their nest

By the hawk frighted.

"Bright in her father's hall

Shields gleamed upon the wall,

Loud sang the minstrels all,

Chanting his glory;

When of old Hildebrand

I asked his daughter's hand,

Mute did the minstrels stand

To hear my story.

"While the brown ale he quaffed,

Loud then the champion laughed.

And as the wind gusts waft

The sea-foam brightly,

So the loud laugh of scorn,

Out of those lips unshorn,

From the deep drinking-horn

Blew the foam lightly.

"She was a Prince's child,

I but a Viking wild,

And though she blushed and smiled,

I was discarded!

Should not the dove so white

Follow the sea-mew's flight

Why did they leave that night

Her nest unguarded?

"Scarce had I put to sea,

Bearing the maid with me,—

Fairest of all was she

Among the Norsemen!—

When on the white sea-strand,

Waving his armèd hand,

Saw we old Hildebrand,

With twenty horsemen.

"Then launched they to the blast,

Bent like a reed each mast,

Yet we were gaining fast,

When the wind failed us,

And with a sudden flaw

Came round the gusty Skaw,

So that our foe we saw

Laugh as he hailed us.

"And as to catch the gale

Round veered the flapping sail,

Death! was the helmsman's hail,

Death without quarter!

Mid-ships with iron keel

Struck we her ribs of steel;

Down her black hulk did reel

Through the black water!

"As with his wings aslant,

Sails the fierce cormorant,

Seeking some rocky haunt,

With his prey laden,

So toward the open main,

Beating to sea again,

Through the wild hurricane

Bore I the maiden.

"Three weeks we westward bore,

And when the storm was o'er,

Cloud-like we saw the shore

Stretching to lee-ward;

There for my lady's bower

Built I the lofty tower,

Which, to this very hour,

Stands looking seaward.

"There lived we many years;

Time dried the maiden's tears;

She had forgot her fears,

She was a mother;

Death closed her mild blue eyes,

Under that tower she lies;

Ne'er shall the sun arise

On such another!

"Still grew my bosom then,

Still as a stagnant fen!

Hateful to me were men,

The sunlight hateful.

In the vast forest here,

Clad in my warlike gear,

Fell I upon my spear,

O, Death was grateful!

"Thus, seamed with many scars

Bursting these prison bars,

Up to its native stars

My soul ascended!

There from the flowing bowl

Deep drinks the warrior's soul,

Skoal! to the Northland! skoal!"

—Thus the tale ended.