Thought Machine (d'Odiardi)

From Kook Science

a.k.a. the Mentograph, a.k.a. the Register of Cerebral Force, the invention of one Edmond Savary d'Odiardi. The device is was intended to demonstrate the existence and influence of mental (i.e. psychic) forces, being in a similar class with instruments such as H. Baraduc's Biometer and Paul Joire's Sthenometer.

Cheiro's Accounts

"The Apparatus for 'Thought Photography and Register of Cerebral Force'" (Cheiro's Language of the Hand, 1897)

- Cheiro (1900), "The Apparatus for 'Thought Photography and Register of Cerebral Force'", Cheiro's Language of the Hand: Complete Practical work on the Sciences of Cheirognomy and Cheiromancy, London: Nichols & Co., p. 158-162, https://archive.org/details/cheiroslanguageo00hamo/page/158/mode/1up

In the earlier pages of this work it will be noticed that I have alluded more than once to the idea of the brain generating an unknown force, which not only by its radiations through the body caused marks and variations on and in the body, but that also through the medium of the ether in the atmosphere every human being was more or less in touch with and influenced by one another (see pages 16, 19, and 21).

When I made this statement some years ago, I did not do so only on an opinion based on the writings of scientists such as Abercrombie, Herder, and others, for I had at that time a tangible proof that such a force did exist through experiments made by my friend, the well-known French savant, Monsieur E. Savary d'Odiardi. I knew that some years before I wrote of this force that this gentleman had invented an apparatus which had been exhibited before the Académie des Sciences, Paris, in which a needle of metal could be moved a distance of ten degrees, by a person of strong will concentrating his attention on it at a distance of from two to three feet.

This little machine was in its infancy then, and although scientists marveled at it in those days, yet there were few who thought it would ever be so far perfected as to be of use in any practical way; but the brain of the man who could think out and invent such an apparatus could not be satisfied to rest at such small beginnings; for nearly five years he patiently worked and labored on, until at last, about two years ago, he triumphed over all obstacles, and constructed an apparatus which completely eclipsed the first machine he had invented, and showed with every person the action of thought in the brain, and which, instead of only being able to move ten degrees, could register 360 in one movement. From that time on he confined his attention to observations of the registering needle with people of different emotions and idiosyncrasies of temperament.

In his electro-medical hospital for the cure of diseases reputed incurable by ordinary means,[1] he had ample opportunities of watching the effect of various temperaments and diseases on this singular apparatus. The result of his work has been that he has been able, by "the observation of cases," to make certain rules to act as a guide in watching the indications of this instrument.

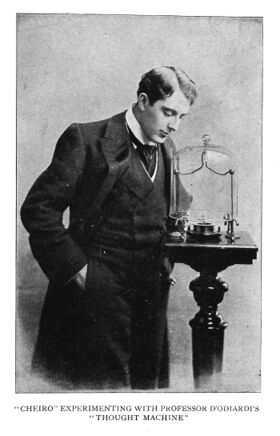

On my return to London, in June, 1896, I had the honor of assisting Professor d'Odiardi with various experiments in connection with this apparatus; and, finally, for the sake of obtaining charts of all sorts and conditions of people, he requested me to collaborate with him in the use of this machine, in order that he might enlarge his scope and field of observation.

After placing notes made from hundreds of experiments in my hands, I brought the instrument to my rooms in Bond Street, and have since then tested it upward of thirty to forty times a day in connection with the various people who visited me.

The proof that the needle in this machine is influenced by a force radiating from the brain is shown by the Professor in his experiments with people who approached it under the influence of certain drugs that injure or stupefy the brain. This is also proved by the fact that though the entire body may be paralyzed, yet as long as the brain is uninjured the needle in the instrument will act as before. He has also demonstrated that "subjects addicted to the habit of having recourse to drugs known as neuro-muscular agents," depressers of the reflex action of the spinal cord, such as chloral, chloroform, bromide of potassium, etc., are the less apt to produce (by looking at the instrument) a deflection or a succession of them in the registering needle; thus demonstrating that the transmission of cerebral force by external radiation is interfered with by the use of such drugs; the absence of the radiation produced by thought-force seeming to point out that the production of thought and the intensity of it is impaired by the ingestion and assimilation of those agents. Not only is such an effect produced by toxic drugs, but also by any kind of intoxication; i.e. by an excess of stimulants, whether in the form of drink or of food. Thus is the stupefying effect of drunkenness and voracity scientifically proved by this registering apparatus.

The same diminution of deflective power in a subject over the needle is caused by anger, violence (after the fit), and by envy, jealousy, hatred (during the fit). A subject being tested in the vicinity of a person he dislikes or hates is shown by the instrument to lose standard; if in the vicinity of a person he likes or loves the standard denoted by the needle is raised. He has also demonstrated that an idiot has no power to deflect the needle in the apparatus, whereas a single look from a person endowed with brain-power may cause a variety of movements and deflections even at a distance of from two to twenty feet.

Among the many interesting experiments made from time to time by the inventor and myself, there is one that has been quoted by "Answers" in an article entitled, "The Most Wonderful Machine in the World"; it is to the effect that upon one occasion a gentleman stood in front of the instrument criticising its action and endeavoring, if possible, to find some explanation of its power. About the same time several other persons entered the room, and in casual conversation one of them mentioned the fact of a sudden fall in the value of South African Chartered Company's shares. No one knew that the gentleman looking at the machine was the holder of many thousands of pounds worth of these shares; but at the moment the drop in the value was mentioned the man's mental emotion caused the indicator in the machine to move rapidly, and register one of the highest numbers that has been recorded by it.

Another curious experiment is that in which one can determine whether out of two people there is one who loves more than the other; in this case the two persons are tested separately, and charts made out of their movements shown by the machine. After they are left together for half an hour they are again tested, and the one who loves the most will be found to have a greater influence on the instrument, while the person "who loves the least will be found to have lost power over the registering needle, in a greater or less degree, according to the effect that has been produced by the other person's presence.

But hundreds of interesting experiments might be cited in connection with this wonderful invention, which have been summed up by the editor of Vanity Fair, December 17, 1896, in which he says: "This curiously interesting machine really seems to bridge the gulf between mind and matter."

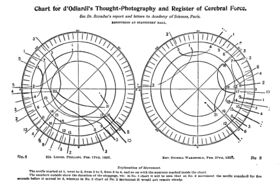

The accompanying illustrations are taken almost at random from the hundreds of charts that have been made from this instrument; they show, in a very striking way, what a difference exists in the radiations of two persons of widely different temperaments. No. 1 is that of Mr. Lionel Phillips, who has played such an important part recently in connection with South African affairs. No. 2 is that of a well-known London clergyman, the Kev. Russell Wakefield. These are good examples of what one would call two strong personalities, entirely distinct and different in magnetism, will-power, etc.

One of the most extraordinary conditions of the machine is that there is no physical contact whatever required (see Pall Mall Gazette, article at the end of appendix). In the regular course of experiments the person to be tested stands within a foot to two feet of the instrument; but if the atmosphere is clear and dry, a person of a strong will may influence the needle at a distance of from ten to twenty feet.

There are no magnets employed by the operator, or electric communication with the needle, except the unknown agent — be it odic force, magnetism, or something still more subtle that radiates from the brain through the body, and that, passing through the atmosphere, plays upon the condenser of this sensitive machine. People have tested this for themselves in every conceivable manner. The greatest unbelievers in this machine have tried in every way to prove that the needle was moved by any other agency but this unknown force radiating from the body, but one and all have in the end admitted that the action of the needle was due to a force given off by the person tested.

One of the leading divines in the Church of England, a few days before this article was written, after seeing the machine being tested in a variety of ways, said: "Such a machine not only would convince one of the influence of mind over matter, but more importantly the influence of mind over mind; for if the radiation of our thoughts affect this needle of metal, how much more so must we not affect the thoughts, ideas, and lives of those around us."

In conclusion, may not then the very force that moves this needle be the very power that in its continual action marks the hand through the peripheral nerves. We know not, and may never know, why this unseen force should write the deeds of the past or the dreams of the future. And yet the prisoner in. his dungeon will often write on the stones around him his name and legend, to be read or not, as the case may be. May not, then, the soul, as a captive in the body, write on the fleshly walls of its prison-house its past trials, its future hopes, the deeds that it will some day realize? For if there be a soul, then is it, being a spirit, conscious of all things, its past joys, its present sorrows, and the future — be it what it may.

1. The Nottinghill Gate Hospital, 30 Silver Street, London, W.

"The 'Thought Machine'" (Cheiro's Memoirs, 1912)

- Cheiro (1912), "Return to London: The 'Thought Machine'", Cheiro's Memoirs: the Reminiscences of a Society Palmist, Including Interviews With King Edward the Seventh, W. E. Gladstone, C. S. Parnell... and Others, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co., p. 153-161, https://archive.org/details/cheirosmemoirsre0000chei/page/153/mode/1up

I WILL pass over many incidents which marked my first visit to New York and go on to my return to London at the fall of 1896.

Within a week of my arrival in my rooms in Bond Street I had the same rush of visitors as before.

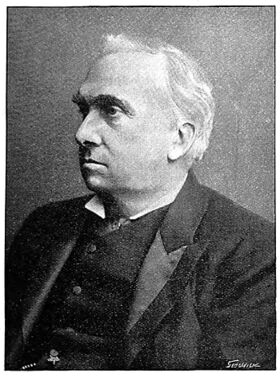

On this occasion I exhibited for the first time a very curious machine which for want of a better name I called a “Register of Cerebral Force,” which had been invented by my old friend, Professor Savary d’Odiardi. Professor d’Odiardi, as many others can testify, was one of the most remarkable specimen that perhaps ever lived, in his experiments on the hidden forces of the body — and perhaps also of the spirit.

He was a descendant of the famous family of the Duke de Revigo, one of the First Napoleon’s great generals. He had the right to use the famous old name and title but he preferred his more simple family name of Savary d’Odiardi.

He was endowed with so many talents that in the embarras de richesses he never knew exactly which to use for the best, and he certainly never seemed to use any for his own personal advantage.

He had had a sensational career. At the age of fifteen the gold medal of the Academy of Music, Paris, was divided between himself and Gounod. Perhaps it was the division of this great prize that hurt his pride, for in the end he did not follow music, except for his own pleasure.

There are many persons living in London to-day who will bear me out if I say that one never realised the power of music until one had heard this old man with the monk’s head play the organ, piano or harps he did at times in his own house in Cromwell Road, Kensington. On these occasions it was often the human harp he swept his fingers over, for I have seen men and women, and some of them the most iron-bound specimens that could be imagined, break down as he told their story in music, and steal up to his side and confess the sealed pages of their life’s history.

He had also studied medicine and had held a distinguished post under the Government of Napoleon the Third. Law he had also mastered, and had fought and won an important case before the French Courts and restored to a woman her husband who had been falsely condemned some years before.

Such is a very brief description of this remarkable man who for years had been one of my best friends in London, and from whom also I learned a great deal of occult knowledge. Rumour said that he had in the many vicissitudes of his career been a member of the Trappist Order, but rumour utters so many lies about men who are in any way above the ordinary that I never gave much credence to this, except on certain occasions, when I knew he was in close communication with the Vatican and the late Pope. Once when I visited Rome he gave me letters of introduction which opened to me the most inaccessible doors in the Eternal City.

Still, we never discussed religion except from the occult standpoint, which was the one common ground that had brought us together[...] When quite a young man, as Edouard Savary d’Odiardi, he had presented the first of these “Thought Recorders” to the Academy of Sciences in Paris and it was investigated there and considered very wonderful.

In this first machine the needle could be willed by a person to move about thirty degrees, but in the one which he afterwards perfected a person, without touching it and standing even at a distance of three feet away, could make the needle move to about 160 degrees of a circle, and more wonderful still could by an effort of his will make the needle stand steady at certain points on its return journey.

This instrument certainly attracted considerable attention. All kinds of people came to be tested by it—so much so that I often sent my friend cheques to the amount of £20 per week as a royalty for my using it. People who took drugs, especially morphine, or who were weak-minded, could hardly make the needle move, and had little or no power over it, while with habitual drunkards it moved in a peculiar jerky manner that was unmistakable.

So much as a prelude to the experiment I am about to relate. One day a man with a very strong will stood before the instrument and at the distance of three feet forced the needle to mark a very high point on the disc. At this point he was holding the needle steady, which was a very remarkable thing to do, when some one came into the room and mentioned to a friend that a certain share that was being actively dealt with on the Stock Exchange had broken half an hour before and had already fallen considerably.

No one in the room knew that the man standing at the machine was interested in the particular stock in question, but the moment the news was announced he lost all power over the needle, and, in spite of every effort he could make, it retreated back to its starting-point.

Only then it was that the man before the instrument turned and confessed to the mental shock the news had given him.

On the previous page will be found illustrations of two experiments, one with Mr. Lionel Phillips and the other with the Reverend Russell Wakefield, which are interesting as showing how the needle in one case worked altogether to the left and in the other case to the right side of the dial.

Among the many well-known people with whom I experimented with this curious machine was Gladstone himself. He was profoundly interested in it, but I shall relate my interview with him later on in its proper place.

- Cheiro (1912), "Interview with Gladstone", Cheiro's Memoirs: the Reminiscences of a Society Palmist, Including Interviews With King Edward the Seventh, W. E. Gladstone, C. S. Parnell... and Others, Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co., p. 168, https://archive.org/details/cheirosmemoirsre0000chei/page/168/mode/1up

I had brought with me my friend Savary d'Odiardi's machine, which I have described in a previous chapter, and placing it on the study table I asked Mr. Gladstone to test for himself if every person brought before it did not affect it in a distinctly different manner according to their will-power radiating outward through the atmosphere.

Standing near the instrument I showed him how far I was able to will the needle to turn; he then tried it himself, and calling some of the servants into the room he quietly tested it with one after another.

When we were again alone I asked him to allow me to take a chart of the movements of the needle when operated on by his will, and I may add that of the thousands of examples I have made with this instrument Mr. Gladstone's stands out as the most remarkable for will force and concentration, as shown by the length of time he was able to make the needle remain at certain points.

Lovell's Account

"Will-Force: Experimental Research Into the Direct Influence of Mental Waves Upon a Material Object" (Light, Mar. 1898)

- Lovell, Arthur (19 Mar. 1898), "WILL-FORCE. EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH INTO THE DIRECT INFLUENCE OF MENTAL WAVES UPON A MATERIAL OBJECT.", Light (London) 18 (897): 139-140, https://archive.org/details/IAPSOP-light_v18_n897_mar_19_1898

In the second chapter of 'Volo, or the Will,' great stress îs laid upon the fact that the exercise of the will, or an act of volition, is the calling into play a force similar to, but not identical with, magnetism and electricity. On page 57 reference is made to a little machine that would respond in movement to strength of will and intensity of thought without physical contact. ‘If you direct a concentrated gaze upon this needle, it will be deflected. A person of weak will, or in bad health, or under the influence of any lowering emotion, will hardly succeed in producing any movement at all. The stronger the personality, the more decided the movement. The rationale of this is given in Chapter III, of “Ars Vivendi.”’ I had not personally seen this little instrument, being convinced that the thing was quite in accordance with the latest researches of science, and being, in addition, of that mental type for which mere phenomena have little or no fascination. The doubting Thomases have their sphere of usefulness, and from their point of view they are perfectly right in not believing till they see. There is really no antagonism between the two standpoints, on the one hand, of seeing first and believing afterwards, and, on the other hand, believing, or reasoning, first and seeing afterwards. The best course to steer is the middle way between the two points. Among my readers, however, there were evidently a considerable number who would like to see before they believed, and latterly I have had very many letters from correspondents, most of which were couched in warmly appreciative terms of the doctrine inculcated in ‘Volo,’ but with the decided statement that they would like to see that little instrument.

Who Invented the Will-Machine?

As a result of the numerous applications, I betook myself to the Editor of ‘Light’ and asked if he had any idea of the the ‘will-machine’ and its inventor. He gave me the address of 30, Silver-street, Notting Hill, W., and in due time I entered into communication with M. D'Odiardi, who was kind enough to give me particulars as to the origin and progress of the invention. I quote the following: ‘M. D'Odiardi resolved, ten years ago, being reluctant to employ vivisection, that he would find an apparatus capable of registering, by simple contact, all forces detected by Dubois Reymond, by means of vivisection. He succeeded, and communicated his discovery to Dr. Baraduc of Paris, who had begged of him to be allowed to use some of his (D'Odiardi's) apparatuses, exhibited by Dr. Huvent of Brussels, and presented to the jury of the International Exhibition of Paris by Professor von Corput, Dean of the Royal Faculty of Medicine of Belgium. When he (D'Odiardi) had finished his apparatus, he began to improve it and perceived that no contact was necessary. A new period began; a new era. Friends of Dr. Baraduc came to see the new apparatus — Dr. Hersch of Brussels, for instance, who wrote an article on the apparatus in October, 1876, in the “Journal d’Homoeopathie” of Brussels.’ I take this opportunity of rectifying an involuntary mistake in ‘ Volo,’ in which reference is made to these two gentlemen as the principal experimenters; whereas, from the information and documents now to hand, there is not the slightest doubt that to Professor D'Odiardi alone belongs the credit and renown of the invention of the ‘will-machine.’

Visit to M. D’Odiardi.

On the morning of February 20th, in response to a cordial invitation to come and see and test the apparatus for myself, I called upon the Professor, whom I found to be a gentleman of about sixty, with a strong, massive face, and what the phrenologists call ‘individuality’ very pronounced in the frontal region. Nature having endowed my own head with a fairly liberal supply of the same commodity, we naturally proceeded to take stock of one another as a preliminary canter, and gradually found our ideas pretty much in accord. To enter fully into the topics discussed would be a most interesting task, but the space at my disposal renders impossible at the present time. Suffice it, therefore, for the present to remark that scientific research is now conclusively demonstrating that Nature's finer forces are infinitely more important for the cure of disease than the crude minerals so abundantly recommended by the orthodox school of medicine. In fact, every dose of sedatives, narcotics, alcoholic poisons, stimulants, tonics, et hoc genus omne, is a bludgeon wherewith to batter down vigorous vitality, until nothing remains but weakness and decay. What harvest of health may man not reap when he realises that electricity is only the steam power within us. There must be an engineer to open the valve. This is, in living beings, will-power. There must be a mode of sending electricity through some channels, and of blocking up all others — this is done by will-power. (From a letter in my possession from Professor D'Odiardi.) When this great truth is realised, then the other great truth will dawn upon the mind, that living in health is an art; in fact, the greatest of all the arts. ‘Away with your nonsense of oil and easels, of marble and chisels,’ wrote Emerson, the mighty seer and prophet; ‘except to open your eyes to the masteries of eternal art, they are hypocritical rubbish.’

The Art of Living.

This idea being the foundation on which the real art of healing disease and of acquiring mental and bodily vigour is founded, and forming the central doctrine inculcated in ‘Ars Vivendi,’ I must beg leave to quote from the latter a few passages showing the rationale of any and every instrument designed to register the vitality and state of an organism for the time being :—

’It is not the actual amount of hard, solid mental work performed during the course of the day that causes the increase of nervous ailments so noticeable at the present time. The root of the evil is want of knowledge of the forces we are constantly dealing with. All mental emotion is so much expenditure of energy, and as mental and bodily energy is strictly proportioned to the capacity of each organism, it follows that every individual can only with safety spend a certain amount of force. This being the case, the part of wisdom is to confine the expenditure of energy to what is strictly necessary in the actual performance of work, and on no account to let any energy run to waste. What I am referring to is the unconscious and totally unnecessary waste of energy caused by want of knowledge of the effect of mental emotion in maintaining or disturbing the equilibrium of health. The strongest physical man could be instantaneously killed by the force of an idea which he was unable to control. The explanation is the change in polarity — a complete swinging of the needle of vitality from the positive pole of vigorous health to the extreme negative of death. Instantaneous effects of this kind are extremely rare; but between the two poles — Life, the positive, and Death, the negative — Health is continually oscillating, till it gradually points to the negative — Decay, Weakness and Death. Every state of mind can be classed as either positive or negative. Some mental emotions approximate more than others to the poles, and some to the equator of indifference; but regarded from the point of view of life, they can all be classed under the two poles, positive and negative. Viewed in this light, then, every mental emotion whatever can be regarded in itself either as preserving of as destroying vitality. Whether or not it succeeds in making its influence felt at the time being by the individual depends upon other considerations, such as intensity or duration of the feeling, amount of vital force to be worked upon, &c.; but, so far as the emotion is concerned, it either lowers and wastes or preserves and increases vital force. As a knowledge of this fact is of extreme importance to all who are exposed to the trials and vicissitudes of life — and from this category who is exempt — I shall endeavour to make it as clear as possible by grouping the principal mental emotions, feelings, or states under the two heads — Positive, or Life-preserving, and Negative, or Life-destroying. After tabulating the various emotions under the two poles, I state: ‘The next step is to learn the art of controlling the mind, so as to avoid as much as possible the negative, or life-destroying, and to acquire as much as possible the positive, or life-preserving, states of mind.’ That appears to me the true and only foundation of a rational system of treatment.

The Register of Cerebral Forces.

Professor D'Odiardi’s instrument isa kind of ‘magnetic needle’ delicately poised and suspended inside a glass dome, so sensitive as to respond to the fine movement in the surrounding ether caused by the emotion of the individual in its immediate neighbourhood. No physical contact whatever is necessary, any more than physical contact is necessary for the transmission of light from one object to another. Light a candle in a dark room, and every article in the room feels ‘the influence,’ so to speak. The candle itself does not touch the objects illuminated, yet the objects and the candle are brought into direct relation by means of the vibratory movement set up in the medium — luminiferous ether. So, with D'Odiardi’s machine, no physical contact whatever is necessary. The emotion of the mind produces in the surrounding ether a movement corresponding to the initial movement. According as this initial movement is positive or negative, that is to say, as it expands or contracts your vital energy for the time being, so does the needle behave. To give a familiar example. Take a weathercock on a house-top. If the breeze is gentle the movement of the weathercock is gentle; if the breeze is violent, the motion must be violent, &c. The following examples will serve in illustration. I thought of three persons in success. In thinking of the first person, my emotion was placid, gentle, calm, and steady — to use the weather-glass term, 'set fair.' Well, the movement of the needle was exactly corresponding, and the Professor, who was sitting several feet away, was able to delineate the state of my mind by watching and recording the movement of the needle. After a little while, to allow the needle to resume its position, I thought of another person. My emotion was of a different kind — turbulent, impetuous, impulsive. Instead of being 'set fair,' the mental atmosphere was 'stormy.' The faithful weathercock showed the same, and the Professor said, 'You were thinking of a person,' &c., &c. After another interval, I thought of another person, and my emotion was entirely different from the preceding two — it was cold, constrained, a saddened memory of the sweet long ago. The Professor said, 'You were thinking of something that is past, something or someone that slightly chills your blood when you call up the image in your mind. The needle by being repelled shows painful emotion, and your power is slightly lowered,' &c.

The Tug of War.

After a few more 'tests' by myself, Professor D'Odiardi took my hands behind my back and placed them in his, to test the effect of the two individual forces when conjoined in sympathetic union. The first effect of joining hands was a plea for mercy on my part, for the Professor in his ardour so squeezed my left hand, and my ring was so severely pressed on my finger, that I forgot all about the machine and everything else in my frantic efforts to disengage the hand and relieve the excruciating pain. Before the next start, I took care to remove the ring, when all was plain sailing. Joining hands naturally resulted in a stronger motion of the needle, but if there was nothing but violent antipathy between us the needle would have been less powerfully affected, I am told. By-the-bye, intending candidates for matrimony can unerringly predict whether they are likely to ‘get on’ well together by the motions of the needle. The last test was a trial of strength between the Professor and myself. We stood on each side of the machine, hand in hand and facing each other, the machine being in the middle. Neither of us touched the instrument. The idea was, which of us would dominate and lead if we were in business together or thrown into frequent contact? A very amusing illustration is given of the relative position of husband and wife by this experiment. Sometimes the husband wins, and sometimes the wife. ‘The instrument,’ said the genial Professor, ‘never lies. I can always tell which of the two holds the sway in the household by watching this needle.’ After this preliminary, we proceeded to test our relative will-strength by one, as it were, pulling the needle one way, and the other, the other way. After a few seconds’ wavering the needle came my way, and I had won the tug of war. M. D'Odiardi said it was not often he was beaten.

To sum up. Thought is force, and will-energy is a force similar to electricity. Science, in the person of Professor D'Odiardi, has constructed an instrument of sufficient delicacy to respond with precision to the movement originated by mental emotion without physical contact. We are now so far advanced in knowledge as to have ocular demonstration of the direct influence of mind upon matter. The character of an individual as a whole can literally be read by 'machinery.' If a person is mentally weak or irresolute or wool-gathering, the motion of the needle corresponds, and no motion is induced by subjects whose brain is affected by 'idiotcy,' stimulants, and depressors of the reflex action of the spinal cord, i.e., neuro-muscular agents such as bromide of potassium, chloral, chloroform, &c. A strong-willed and healthy person, on the other hand, is indicated infallibly by the strong and steady movement of the needle.

My next séance with Professor D'Odiardi was still more interesting, for, acting on the suggestion of Mr. Dawson Rogers. I tried the effect of various 'abstract' emotions, such as love, fear, &c.

(To be continued.)

- Lovell, Arthur (26 Mar. 1898), "WILL-FORCE. EXPERIMENTAL RESEARCH INTO THE DIRECT INFLUENCE OF MENTAL WAVES UPON A MATERIAL OBJECT.", Light (London) 18 (898): 150-153, https://archive.org/details/IAPSOP-light_v18_n898_mar_26_1898

The Province of Science.

A few years ago, and, in fact, even now in certain quarters, genuine science had no more impassioned, inveterate, and bitter enemy than the self-styled representative of 'Modern Science,' par excellence. He constituted himself the sole arbiter of knowledge. He was the despot, to offend whom was to commit the unpardonable sin, But in the last few years he has had so many slaps in the face, not to mention knock-down blows, that he is rapidly recognising his true sphere in life, which is that of finding out what is hidden, not of denying that there is anything hidden simply because he cannot see it. ‘Strictly adhering to this idea of science, we cut off very sharply an immense portion of what has been called science by the scientific man. Take, for instance, the attitude of what has been called “modern science” towards the world of occultism that is, what Tyndall called “the subsensible world.” It has been one long cry of derision and scoffing. Now the tables are turned, and it is the fashion to admit what then it was the fashion to deny and denounce as “unscientific.” Science proclaimed such and such a thing impossible. Science, indeed! It was not proclaimed impossible by science, which is but a Latin word meaning knowledge, but by the very opposite of science — crude ignorance and arrogance. — If such and such a fact can, and does occur, the province of science is not to deny, but to find out exactly how it occurs.’ (‘Volo’).

M. D’Odiardi has struck me as one of the genuine, unsophisticated specimens of the real scientific spirit. In stead of denying their existence, he succeeds in registering unseen forces acting within and around us, with which, ignorantly or otherwise, we have to deal every minute of our lives.[⁎] On the skilled manipulation of these forces depends our success or failure, our pleasure or pain, our happiness or unhappiness; therefore, the more we know of them, the more are we likely to benefit ourselves as well as the whole human race. If we can be made to realise, by ocular demonstration, that our states of mind are continually building us up or pulling us down, common-sense tells us that it is unwise to indulge in them indiscriminately, and then to blame somebody else for effects the causes of which we have set in action ourselves. Remember always that it is your own organism on which these feelings and moods impinge. Suppose, for example, that a person is under the influence of violent hatred or jealousy. We will say A hates B. Very well. B is undoubtedly affected by this violent emotion projected from another organism, but it does not end here — or, for that matter, it does not begin here. The organism of A is in a state of violent commotion every time he is thinking of B. I am referring now to the ordinary person, not to the advanced occultist, or what is called ‘The Black Magician,’ who, though evil, has trained himself to be a master of the art, and can launch out a current without its recoiling upon himself, at all events for a considerable time. The ordinary person is by no means a black magician, indulges mental moods simply because he cannot help them. If he can realise that hatred or anger actually lowers his vitality, he will gradually get accustomed to subduing them.

The Tests.

In going through the following tests of the effect of various mental states upon D’Odiardi’s apparatus, I took care to jot down in my note-book a certain emotion upon which I was going to concentrate, without telling the Professor what that emotion was. This was done to prevent the possibility of suggestion acting upon his mind and making him see more in the movements of the needle than was actually indicated to the trained expert. While I directed a concentrated gaze upon the needle at the distance of about a foot, Professor D'Odiardi was sitting, pencil and paper in hand, at the distance of about ten feet from the apparatus.

I.— Calm. Peace of Mind.

Subjective State.— I approached the instrument in a calm and peaceful frame of mind, which gradually deepened into gentle spiritual aspiration. I thought of the quiet calm of the cloister, with the minds of the inmates turned towards God in silent prayer; and then mentally repeated the sacred word, 'Om,' round which clusters such a depth of meaning, when rightly thought of. I was drifting away into the islands of the blest, when the Professor broke in with his

Objective Observations.— 'The whole of this test except the first movement of the needle indicates “Calm Thoughts,” unconnected with any important or emotional subject, such as “What shall I do to-day? Where shall go?” But the first movement was slow repulsion lasting forty seconds, followed by a stoppage of twenty seconds during which the needle remained inactive. You had been a moment before thinking of an emotional subject; and to master the excited activity in your mind, you were obliged to exert your will-power to stop the current of your thoughts and still your mental waves. That is why the needle was repelled very slowly during the time needed for that concentration of feeling. Then the next movement towards you was a very slow and steady sweep of one hundred and eighty degrees in the inverse direction of the hands of a clock until the needle pointed to the middle of your chest, and stopped there for twenty-five seconds: then there was a slack in your thoughts for a moment during which the needle was resuming its normal position, when a new thought occurred again which made the needle point to your sternum, where it remained immobilised like your thoughts, until you came back to your seat. This test might be characterised as one of “Abstraction.”

II.— Hatred.

Subjective State.— The idea with which was engaged now was hatred of an imaginary enemy and fighting to the bitter end. The Professor had in the former interview remarked that I was of too sympathetic a nature to make a good test for a criminal or detective, and from a most ingenious classification of the different tones of voice — a subject which he has studied, he tells me, for years — he claims to be able to tell what is the dominant characteristic of every individual. Determination and perseverance and resolute will he put down to me as the leading traits of my mind. Whether rightly or wrongly, he said I could not be capable of hate, pure and simple. I make these remarks, for I feel I did not get a perfect test for hatred. After my opponent was pinned down, the emotion of hate subsided, and I had to begin my imaginary struggle over again to keep it going. This very conflict between hatred and pity in my mind spoiled to a certain extent the ‘hatred’ test.

Objective Observations.— The very rapid initial repelling movement of the needle indicates “hatred.” Ninety degrees were run through in four seconds’ time, and the stoppage of the needle during thirty seconds of the ninety degrees of the arc indicates a localisation of the thought on the same feeling, this localisation being due to corollary ideas connected with retaliation, ie. vengeance. The ninetieth degree belongs, when the needle stops there altogether, without coming back or going further, to the test of a criminal or a detective, both of whom, strange to say, have the same test. A criminal hunts honest people as his game; a detective hunts criminals; and both must be deprived of pity for going through their task. I have never yet had an opportunity for testing a murderer, but only thieves and swindlers. I have not the slightest idea of what the test of a murderer might be. At the end of this test the needle came back very slowly and reluctantly, showing that irradiation of cerebral force of great energy does not cease as soon as the intense thought which has produced it has been given up by the subject tested.’

III.— Fear.

Subjective State.— In this test I felt that I was much more successful, and was able to feel the emotion, as it were, in real earnest, for I know what fear is, and also what non-fear is. Fear is the extreme negative pole, the contrary of faith and courage. ‘Courage is the soul's conviction that man is infinite; fear is the denial of this, and the belief that man is but a worm, to be trodden upon by a malignant fate. Fear is the principle called “evil,” and when this principle or idea becomes incarnate in a form suitable for the imagination to grasp, then arise terrible spectres of evil spirits, varying in names and attributes according to the development of the mind. To free himself finally and for ever from the bonds of fear is the end for which man is working. It is a difficult struggle, and we are apt to halloo long before we are out of the wood. To find an absolutely fearless man is the rarest of rarities.’ (‘Ars Vivendi,’ p. 59.) The immediate and direct effect of fear is to contract and paralyse mental and bodily powers. A very fine illustration is given in Lytton’s ‘Zanoni,’ in the scene where the pupil Glyndon, having disregarded the master's warning, tries to force himself onward without having undergone the requisite training beforehand. Progress to be lasting must be slow, steady, and methodical; otherwise the mind at some critical moment is sure to collapse like a top-heavy building raised on an insecure foundation. The description of the dread ‘Dweller on the Threshold’ in ‘Zanoni’ is a great truth veiled in the garb of fiction. Adopting a term dear to the soul of the Psychical Research investigators, I ‘visualised‘ the whole of the scene in Mejnour’s castle, and for the time being I was Glyndon standing before the awful phantom. ‘The casement became darkened with some object undistinguishable at the first gaze, but which sufficed mysteriously to change into ineffable horror the delight he had before experienced. By degrees, this object shaped itself to his sight. It was that of a human head covered with a dark veil, through which glared with livid and demoniac fire, eyes that froze the marrow of his bones. His terror, that even at the first seemed beyond nature to endure, was increased a thousandfold, when, after a pause, the Phantom glided slowly into the chamber. It seemed rather to crawl as some vast misshapen reptile; and pausing, at length it cowered beside the table which held the mystic volume, and again fixed its eyes through the filmy veil on the rash invoker. As clinging with the grasp of agony to the wall — his hair erect, his eyeballs starting, he still gazed upon that appalling figure — the image spoke to him,’ &c. I could feel that the influence of this emotion was to depress and lower all the forces in my organism. If it was pushed still further, I might get so weak as not to be able to stand up, much less resist the advance of a malignant foe. That is the lesson taught in ‘Zanoni.‘

Objective Observations.— ‘In this test there were only three very slight movements of very small amplitude, the first being slightly repellent, the second slightly attractive, the third and last being repellent again. All these movements were most sluggish, running through a few degrees only on each side of the Zero. But the peculiarity of the needle in all the tests I have taken of you hitherto is that the needle never stops except to resume its course afterwards in the reverse direction. There is no intermittence unless the whole of a force has been spent, and it is then replaced by a force of another nature. This is an indication of perfect co-ordination of thought, and is rarely met with in the same degree as in your tests. As there is no medal without two sides, I will mention en passant that it also shows a tendency somewhat akin to that attributed to the Bretons of France, of whom it is said that the only way to take an idea out of their head is by means of a cannon-ball! It is why the Bretons have always heroically fought for their God and their King. This test is the test of "Fear and Sorrow."'

With reference to the above remarks regarding the Bretons, I am proud to say that I belong to the great Celtic race, and that the Bretons of France and the Cymry (or Welsh, as they are erroneously called by the Saxons) are very closely allied, as is abundantly proved by the researches of Professor Rhys and other comparative philologists. As to the cannon-ball, all I can say is that it could shatter my brain to pieces; but as to getting an idea out of my head, that is quite another matter.

IV.— Love.

Subjective State.— This time I was under a totally different emotion from the last. It was the feeling of universal love for mankind, the brotherhood of the race, and individual kindness and goodwill. Being habituated to concentration, I could easily maintain my thoughts in this groove for any length of time I chose.

Objective Observations.— ‘The movements in this test are only connected with generous passions, and show love of person already possessed; the calm steadiness of the movements and absence of impulse showing deep and tender friendship, and not a mere brutal passion; the amplitude of the movements, the area where they took place, and the length of stoppages opposite the sternum showing duration and constancy, the absence of jerks excluding the idea of mere brutal passion.’

V.— Faith in Difficulty and Darkness

Subjective State.— The idea which animated me this time was that of steady faith in the midst of difficulty and opposition. The images which I called up in my mind were those of the martyr at the stake, whose faith in the cause he maintains is unshaken; I also visualised the beautiful poems of ‘Excelsior’ and ‘The Light of Stars.’

Objective Observations.— ‘This test has puzzled me greatly, I find “doubt” and “love” expressed clearly. Doubt in love causes jealousy, and the succession of movements in this test does not indicate jealousy any more than their direction and amplitude do. “Want of faith in a beloved one” is all I can say, and to my great annoyance I can find out nothing else.’

This test appears to me, in a sense, to be the most satisfactory of all, for the very meagreness of the Professor's remarks, together with his inability to get more than a certain clue to my mental action, speaks eloquently. Bearing in mind that all mental emotion must come under one of the two poles — positive or life-sustaining, and negative or life-destroying — we can easily see that ‘faith in difficulty’ corresponds in effect, at all events so far as any mechanical recording apparatus is concerned, to ‘doubt in love,’ or, more properly, ‘love with a mixture of doubt.’ Love and faith belong to the positive pole; difficulty and opposition must produce a certain amount of doubt in the bravest-hearted at moments. The very strongest spirit, if ‘in the body pent,’ must partake, if only in a very small degree, of the weaknesses and trials of the physical world. In this test there were the two different emotions of faith on the one hand, and difficulty and darkness on the other. The vibrations of the one emotion must be entirely different from those of the other, and there is a struggle between the two to get the mastery. One moment faith will suffuse everything with its radiant face, another moment and the horizon is darkened, the heavens are brass, and the spirit is utterly prostrate. One moment the individual doubts the one he or she loves — every movement, every act looks suspicious; the other moment the vibratory chord of love is struck, and everything is changed.

Summary.

The above experiments with D’Odiardi’s Register of Cerebral Forces have borne in upon me with renewed weight the absolute necessity of understanding the influence of mental emotion, and the finer forces of Nature, upon our daily lives. Here we are complacently weaving the web of our life day after day, hour after hour — nay, minute after minute. Our bodies are incessantly changing for better or for worse — with the immense majority for worse. Our ‘too, too solid flesh’ is every moment ‘thawing and resolving itself,’ and, according to the very latest scientific research, completely changing in about six months. Every impression made upon us tells its tale; the house we live in, the associates and friends we mingle with, the books we read, the stories we tell, the sights we see, the emotions we feel, however transient they are — added up and totalled together make the visible and tangible us. Real health implies something infinitely more than what is taught in the medical schools. What is it but the manipulation of Nature's forces by the individual will to build up a beauteous home in the physical world? Even now advanced science pointing the way to health by demonstrating that there is no disease but cell disease. What is the cell but the result of the working of the two poles — the positive or active and negative or passive? The real meaning of freedom of will is that spirit can effect a change of polarity by volition. What we call ‘Nature’ and ‘the natural world’ is but the play of these two poles. Science, or knowledge, is only a means to the great end of bringing the periphery of the circle into accord with the centre. The perfection of science would be to record mechanically the effect upon our lives of every passing feeling, so that the most dull and the most sceptical can actually see for themselves that as they sow, so they reap, and that they must look for corn of the same seed as they sow. To stand with open mouth at such an apparatus as D’Odiardi’s and cry ’wonderful’ is not enough. Let us begin to resolve to control for our benefit the subtle forces we are now crudely tampering with, and more often than otherwise burning our fingers over. Let us reverently regard ourselves as centres of energy whose potentialities point to infinity, and whose kingdom, prepared ere the foundations of the world, is the kingdom of health and peace and happiness.

* He has a 'register of electricity in the human body, giving exact amount of power in the subject tested, and another apparatus which, combined with the other registers, indicates with unerring precision what diseases may be lurking in the organism, so that the prevent of insidious disease becomes easy, as incubation may be prevention at onset.'

Critical Responses

"Report on Instruments Alleged to Indicate 'Cerebral Force'" (JSPR, June. 1898)

- Fox, St. George Lane; Wallace, A. (Jun. 1898), "REPORT ON INSTRUMENTS ALLEGED TO INDICATE 'CEREBRAL FORCE' AND THE 'PSYCHIC ACTION OF THE WILL'", Journal of the Society for Psychical Research (London) 8 (150): 249-250

Several forms of apparatus, including E. S. d'Odiardi's, Ditcham's, etc., have been examined, all of which consist essentially of a light body suspended in a glass bell jar by means of a silk or other fibre in such a manner that a very slight force exerted upon it from one side or other causes it to rotate about the point of suspension.

In the instruments inspected, the bodies suspended were made to move by the approach of the whole body, by the hand alone or other part of the human body, or by heated bodies, as a glass of hot water. The air currents set up by the warmth or movement of the whole body or the hand were quite sufficient to account for any deflection that resulted in the suspended body.

That air currents were formed was clearly shown by means of clouds of smoke. The approach of a slightly electrified object would, of course, exert a certain amount of force upon the suspended body and might induce some movement apart from air currents; but there was no evidence whatever of the exercise of any "psychic force." It should be added that neither in the suspended body itself, nor in the method of suspension, was there anything in any way striking or novel, or other than is perfectly familiar to every practical physicist.

These instruments do not contribute to our knowledge of "psychic force," as it is obvious that in order to make any satisfactory test for its presence the various forces well known to the physicist must be eliminated altogether or duly accounted for in any experiment that is made. The "inventors" of these "psychic" apparatus are evidently quite ignorant of the methods of scientific research. The claims made regarding d'Odiardi's instrument, in a book called Cheiro's Language of the Hand, that the deflection of the suspended body is a means not only of demonstrating the existence of "cerebral force" but of registering its amount, are entirely without foundation; and we warn our readers against placing the slightest credence in the allegations made by "Cheiro" and other persons that the instrument in question records the action of forces other than those well known to physicists.

Press Coverage

"Thought Machine Records Mental Emotion" (The Phonograph, Oct. 1896)

- "Thought Machine Records Mental Emotion", The Phonograph 1 (10): 5-6, Oct. 1896, https://archive.org/details/phonoscope13hunt/page/n174/mode/1up

In the domain of psychic phenomena a "thought machine" is the latest thing out. It has been described by those who have seen it in action as the most wonderful bit of mechanism in the world. It is so small that it can be carried very easily in an ordinary hat box. It acts like a sentient thing. The mechanism of sympathy seems to be finely exemplified in its mysterious power. It can read your thoughts whether you be love-sick swain or a bold, bad man intent upon some dark deed of conspiracy and crime.

The poet who has not the gift of uttering the thoughts that arise in him will hail this product of inventive genius with unfeigned delight, for it will faithfully record the sublimest emotions and the most sublimated creations of poetic fancy. But it will do no thinking or transcribing for the man who has no thoughts of his own. It does not essay to grind out nice, happy, original thoughts at so much per think, as the professional story writer grinds out his pages of manuscript.

It just gives you a photograph of the inside of your head in motion. If Governor Tanner could have been brought in proximity to it when he first heard of the hisses that greeted his name at Nashville, the wonderful thought indicator would doubtless have fluttered in a most extraordinary manner. If one of these thought machines were to be placed in the city council, on an occasion when some municipal jobbery is to be rushed through by the gang, it is believed the needle would remain almost stationary most of the time, though it might show a confused agitation during the heat of some of the debates. It is proper to add, in explanation, that an idiot has comparatively no influence over the machine, and can hardly cause the indicator to move at all; but in the presence of an insane person the needle turns hither and thither in aimless confusion.

This miraculous instrument, which accurately registers intensity of thought, power of concentration and peculiarities of temperament, is at the Auditorium Hotel, Chicago, Ill. It is in charge of "Cheiro," the well-known authority on the science of the hand, who is Count de Hamong in private life. It is the product of the inventive genius of M. Edmund Savary d'Odiardi, a French scientist, who had the honor of presenting it at the French Academy of Sciences. The inventor has conveyed to "Cheiro" the sole and exclusive right to use the machine in all countries in the world. It is technically described as ' 'an apparatus for thought photography and the register of cerebral force." There are only two sets of these marvelous machines in the whole world — one at the Nottinghill Gate Hospital, London, where it is used by M. d'Odiardi to record the phenomena of mind in various diseased persons, and the one used by "Cheiro," in his travels and experiments. It is sometimes popularly called the mentograph.

Imagine a small clock dial placed on top of a neatly carved pillar and protected from the air by a glass dome, and the thought machine is before you so far as external appearance goes. The interior construction, which is of the most delicate and intricate character, is a profound secret, locked up in the inventor's cabinet. In the outer circle of the dial minute divisions are described, running on either side from zero up to 180 at the opposite pole. There is no physical contact with the mechanism whatever; you simply look intently at a needle suspended above this dial, and according to your powers of concentration and will is your ability to deflect it one way or the other. Two machines are used in scientific experiments, one to verify the other. The wires used in the construction are made of pure gold.

It is acknowledged by most of those who have witnessed the phenomena of spiritism produced under rigorous tests and conditions like those applied by the London Society for Psychical Research that there is a dynamic force residing somewhere which is capable of moving ponderable objects without physical contact, and that this force, whatever it is or from whatever source it emanates, possesses intelligence, oftentimes to a remarkable degree. This intelligent force must either emanate from the spirits of the dead or from the spirits of the living. But it is not claimed that spiritism has anything to do with the thought machine. But the dynamic force that moves its indicator to sway without physical contact is the one strange and mystifying thing about it.

There is a cerebral force or fluid which acts upon and within the body of man; this same mysterious force through the medium of ether seems to act upon the mentograph. The needle sways and vibrates to ore side or the other, changing its position almost constantly, as the thoughts of the subject, before it takes on constantly different shades of color and meaning, and the expert by his observation of the dial • is able to furnish a complete chart of the person's mental and emotive nature. Telegraphy and hypnotism have generally ceased to be regarded as proceeding from supernatural agencies. They are now recognized as powers inherent in mankind, and are largely employed to explain other phenomena. There seems to be a kind of telegraphy in operation between the mentograph and the person who stands before it and fixes his thoughts upon it.

Weird and uncanny is the first effect produced on one who stands before the apparatus for measuring and registering human thoughts. It is said that it has power to indicate so accurately the depth of the thoughts and the varying emotions, that if the person operated on by it were first to read a page from Child's school book, then suddenly change to an abstruse scientific work, the machine would register exactly the amount of brain power required to understand each of the two books.

Sometimes when a person is under the spell of the thought reader the indicator will spin round at a tremendous rate, and stop at some high number — say 175 or 180 — then perhaps suddenly return to number 8 or 9. Each time the indicator advances to a number and then falls back, the scientist who is making the test writes down the number indicated. It is the scientific interpretation of these numbers that furnishes a chart of the mind and temperament of the person examined.

The chart of Gladstone was written in this way. The grand old man, the world's greatest statesman , was given an experiment with the machine by "Cheiro" at Hawarden Castle, and was greatly interested in its mysterious workings. The power of his concentrate*' thought brought the indicator half-way round the dial — the limit of its operations — and held it at different points in that vicinity for periods varying from two to twenty seconds. Another noted personage who had an interesting interview with the thought machine in England was Mark Twain.

It has been tried by several well-known Chicagoans with varying results. In one case a man fixed his eyes on the dial and concentrated his whole attention on the indicator; in less than twenty seconds the instrument appeared to him to indicate that the subject was a chronic victim of three different noxious drugs, and finally that he was a pronounced criminal of the most vicious type. He was naturally very much distressed until "Cheiro" informed him that he had been looking at the wrong end of the indicator. He felt better when this was explained, and a chart was given him, which, he confessed, revealed his character with the most surprising and humiliating accuracy.

The mentograph measures thought and intelligence so accurately that it is impossible to guess what marvelous things may be accomplished by it in the future. For example, a few months ago, in London, a man stood in front of the machine criticising its action and endeavoring, if possible to find some explanation of its power. About the same time several other persons entered the room, and in casual conversation one of them mentioned the fact of a big drop in the shares of the South African Chartered Company. No one knew that the man looking at the machine had invested many thousands ol pounds in these shares; but instantly the decline in the value was mentioned his emotion caused the indicator of the mentograph to swing round and register one of the highest numbers that has ever been recorded by it.

Not only will this apparatus register intense emotion relating to money-losses, but according to the theory of the inventor and the experiments of "Cheiro" himself, it will reveal the secrets of love and lay bare the human heart as well. When testing the intensity of one person's love for another separate charts of the characters and minds of the two persons are first made. Then the lovers are placed in a room near two of the mind-reading machines and left for half an hour or so; they are requested to enter into conversation, as the divine passions are more easily stirred by this means. At the end of thirty minutes the machines are again examined and the charts of each are compared with the first charts. Then the one who registers the highest degree of emotion loves the most, and the other the least. Judging from these deductions, young men and young women desirous of marrying for money and position, and not for love, will have a rather uncomfortable time in the future if these thought machines should come into general use.

The thought reader might have been introduced in the Luetgert trial with good results. The most amazing quality of the machine is said to be its capacity for judging, in some cases, of the guilt or innocence of a person accused of crime. In one instance several men were arrested on the charge of highway robbery, and the man who had been robbed was called to identify, if possible, the one who had assailed him. The suspects were brought into a room, one after another, and the mentograph was placed within a foot of each. Some of the prisoners registered intense nervousness and emotion. But when the guilty man was con. fronted by his victim the indicator whirled around in a manner which left no doubt as to his identity. It was subsequently proved in open court that the man indicated by the machine was the guilty person.

Those who have read the story published by the first Lord Lytton in Blackwood's Magazine entitled "The Haunted and the Haunters, or the House and the Brain," will examine this mechanism with exceptional interest. There is, as all know, a popular belief that certain houses are pervaded by a mental atmosphere, so to speak, which corresponds to the mental condition of those who have inhabited it. The air is surcharged with their emotions, longings, sorrows and mental peculiarities. May not such force radiate from a living person to a delicately constructed mechanism? Another book that will interest observers of these phenomena is Du Maurier's striking story of "Peter Ibbetson," based on the contention that two subjective minds whose bodies are far distant may communicate with each other during sleep.

The value of the mentograph's deductions over ordinary evidence lies in the fact that, no matter how well a man may disguise his emotions or how calm and self-possessed he may appear outwardly, the mechanism still records his inner feelings.

Another thing that the mentograph will tell of is the influence of a mesmerist. If a person under the influence of a mesmerist be tested, the character of the mesmerist himself is indicated and not that of the subject in front of the dial. As persons subject to hypnotism are usually of weak character, a scientist can easily see that the person tested does not really possess the will power recorded by the machine, and the fact that they are under hypnotic influence is easily discovered.

It is a remarkable fact, too, that an idiot has comparatively no influence over the machine, and can hardly cause the indicator to agitate at all while a person who has become insane causes the needle to whirl and flutter in a confused and erratic manner.

The thought-reading machine has been private ly exhibited and tested daily for two years at the Nottinghill Gate Hospital, London. Subjects addicted to noxious drugs known as "neuro-muscular agents," depressers of the reflex action of the spinal cord, such as chloral, chloroform and bromide of potassium, alcohol, etc., are the less apt to produce (by looking at the instrument) a deflection or a succession of them in the registering needle; thus demonstrating that the transmission of cerebral force by external radiation is interfered with by the use of such drugs; the absence of the radiation produced by thought-force seeming to point out that the production of thought and the intensity of it is impaired by the ingestion and assimilation of those agents.

Dr. Luys of the Charity Hospital, Paris, by means of the X-rays, recently photographed these radiations from the brain and in every way corroborated the experiments made by this instrument — viz., there was no radiation from the brain of an idiot, and the same drugs that affected the machine also affected these radiations in a similar manner.

By collaboration with "Cheiro," M. d'Odiardi will obtain observation charts of all classes of healthy individuals, whereas in his hospital work he is able to obtain mental photographs only of diseased persons. From this data it is the intention to compile a work which the projectors hope will prove of great scientific value. In conclusion! it may be said that the curiously shaped needle, or indicator of this wonderful little piece of mechanism is influenced in diverse ways by the radiation of brain force at distances varying from one foot to twenty feet.

"AN ELECTRIC LOVE MACHINE." (Savannah Morning News, 10 Oct. 1897)

- "AN ELECTRIC LOVE MACHINE. Thousands of Engaged Couples Visit the Laboratory of Prof. d'Odiardi. To See Who Loves Most — Psychologist Experimenting to Learn if Old Maids Can Fall in Love — Other Uses For the Machine.", Morning News (Savannah, GA): 18, 10 Oct. 1897, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86063034/1897-10-10/ed-1/seq-18/

London, Oct. 2. — The French Academy of Sciences has in its possession the most wonderful little instrument ever invented. It is an electric love machine, and its name is not half as remarkable as the work which it does.

This machine is the invention of Prof. Savary d'Odiardi of Silver street, Nottingate Hill, London. The professor is very well known in France and England. He received the medal of honor from the French Humane Society for his devotion to humanity, and a medal from the national commission for national rewards for his works and inventions.

Prof. d'Odiardi calls his electric love machine a register of cerebral force. He says it indicates every motion and reads every thought, but it is strongest for love and hate.

While the Chicago Human Nature Club is giving its trolley parties and receptions for the mating of males and females, Prof. d'Odiardi's little instrument is doing its work much more quietly, and experts say, more accurately. The Chicago Human Nature Club works from phrenology. Heads are read, and husbands and wives selected, but the d'Odiardi instrument works by electricity, and is controlled by thought.

When you come near this instrument you immediately notice that the needle begins to swing. This, to the man who can read it, means something; and if you are provided with a chart you can read from the needle your own thoughts, just as well as you can translate them from your own mind.

The instrument itself is very unpretentious. It consists of a thread, from which is hung a tiny hatchet-shaped instrument, which has a sensitized needle. This swings over a metal disc, inscribed with degrees. The instrument stands upon a pedestal, and, it is said, looks not unlike a piece of bric-a-brac.

Every thought is registered by the needle, with or without the wish of the gazer; and unconscious thoughts are told as well as conscious ones. Below the needle is a disc which records the movements of the needle by absorbing all forces other than brain waves.

People who have small brain power hardly influence the needle. Drunken men and idiots scarcely deflect it, because they have so few brain waves. Strong people cause the needle to vibrate rapidly, and when Mark Twain and Richard Croker tested the machine they found that the needle swung with such force that the degree upon the metal could not be recorded.

If you feel loving towards a person the needle comes toward you. If you feel hateful, it swings away. This fact is of the greatest human interest, because it suggests so much.

The professor uses his instrument also to cure diseases. He studies the action of the mind, and notes its influence upon the body. This he afterwards treats with his own electric cure.

But the instrument can be made of more general value as a love machine than it can by curing the sick. All people feel or taste of love in some way and there is no period of life when a man or woman is love proof. From the age of 16 to 60 the vein of love runs through every human being, and there are many cases in history of those who have felt its effects below and above these ages.

This machine can fill the greatest human want, namely, that of supplying a cure for the greatest malady that is known, love-sickness!

Hundreds of people have tested this love machine and have found it to work quickly and accurately. It is useful to three classes of people.

Lovers who want to find if their sweet-hearts are devoted to them. Young men can take their sweethearts there and place them opposite the electric needle. The man stands at one pole and the woman at the other. Both concentrate their thoughts upon it. The young woman thinks intently of the young man and the young man thinks intently of his sweetheart. This is an anxious moment. Both are awaiting the turn of the needle. The one with joyous anticipations, the other anxious. Slowly and slowly the needle begins to move, and with a few vibrating movements it swings itself towards the one whose love is the strongest. Hate deflects the needle, and if the woman hates the man the needle swings far away from her. If, on the other hand, they love equally, the needle stands still.

Married women visit Prof. d'Odiardi to find if their husbands still love them. There comes a time in the life of every married man when he must stay out late at night. This the wife construes in different ways. It may be business, it may be pleasure. If the latter, he no longer cares for her. By taking him to Prof. d'Odiardi's machine she can tell if he still loves her or if his love has turned to indifference.

The machine is also used by psychologists, who take old married people there by way of experiment to see if love is permanent. They also have experimented somewhat with old maids to find if they can love later in life. If an old maid marries, say about the age of 40 years, psychologists who are interested in the electric love machine endeavor to get her to the laboratory of Prof. d'Odiardi, to determine whether she married from love or other motives.

This machine can be made useful in divorces, to see if either had remained constant in love. It can be used in case of separation, to determine the custody of the child. If the needle swings toward the mother instead of the father, her love must be stronger than his. In that case both would have to think intently of the child to influence the needle. Of course, both would endeavor to put force upon it, and the needle would be a true indication of the cerebral radiation of love.

There are many other adaptations for the Electric Love Machine. Phrenologists claim that no one should marry without consulting those who can read bumps. This may be true. The love machine is also a good indicator, and the man who consults both of these authorities, and finds that in each case his lady love registers true to him, need have no objection to her on the ground of false motives.

Prof. d'Odiardi has been an electrician since the age of 10, when he invented an electric apparatus. He is a cousin of the late Dr. Cruvelhier, who was the physician of King Louis Philippe. He is of unquestioned standing in the French and German schools, and all of his discoveries and inventions are treated with respect, and not with incredulity. Edward Grey.

"SWAYED BY THE WILL" (Los Angeles Herald, 24 Oct. 1897)

- "SWAYED BY THE WILL", Los Angeles Herald (Los Angeles, CA): 26, 24 Oct. 1897, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042461/1897-10-24/ed-1/seq-26/

LONDON, Oct. 10. — (Special Correspondence to The Herald.) "Exercise your will," said Copernicus, "and your mind will grow apace." Even this ancient sage never dreamed that which to him would have seemed a miracle, a machine that would enable any person to strengthen his will by exercising it, would be invented. Nevertheless such a machine has just come before the public and it has been proved by tests that it will do exactly what is claimed for it. No name has ever been given this remarkable invention, but it can honestly be called the wonder machine of the century.

Think of a contrivance of inventive genius that actually moves or remains stationary. Just as you may will, just so long as you give it your attention. This strange creation was conceived in the brain of a French savant, M. Savary d'Odiardi, who is at present in London. He has made the idea this machine represents and the human emotions the study of his life, and knows more of the real facts concerning humanity than probably any other savant of the present day. He has, indeed, practically solved the problem of mental telegraphy, and with this machine approaches nearer to one of the unknown forces of nature than has any one else for at least centuries.

He declares that we are still in the twilight of experiment, and with this remark ushers you into the presence of that tiny little machine that before you are done with it will fill you with uncanny thoughts and make your surroundings seem eerie for many an hour. To be technical for a moment, let us call the little instrument a register of cerebral force, or, in other words, a machine that indicates to us just what we think.

A little pedestal stands in the inventor's study, workshop or laboratory — whatever you may please to call it — and upon this rests a bell, the home of mystery. Beneath this stands a metal disc inscribed with degrees, and directly over this disc, suspended by a wire so delicate that the thought of Damocles' sword comes to you at once, is a sensitized needle, fashioned very like a small hatchet. Here is the cerebral register, the interpreter of emotion, the will exerciser.

Look at it carefully, and immediately it moves. Affected, despite your assumed indifference, you wonder what force it can possibly be that is making that needle sway first this way and then that. Gray-haired M. d'Odiardi leans on his stick and smiles on you so kindly that you never think of possible ridicule or amusement at your ignorance. "It is your mind that moves the needle," he says. "The needle tells me that you are wondering, but as your face reveals that also, it is not surprising that I should know. Now look at the needle's point." Immediately the tiny steel swings towards me.

Just a second, and the needle swung slowly back. "Will strongly," said the inventor. "Do that, and you will hold the needle facing you." I did so, and lo! once again the needle slowly swayed towards me, and for a brief moment I held it directly before me purely by force of will. Then it swung away. It was apparent that my will was not capable of sufficient concentration for a longer period; or at least, not under those conditions.

"You would be surprised," said the inventor, "if you could see the effect that constant relation with this machine has upon the mental powers of a person. I do not exaggerate when I say that let a man who lacks concentration and stability of will do every day just what you have done with that machine for a month, and he will have more decision than he has ever had in his life. You see, it is not a theory, because here is the machine, and here are you to prove that so long as you concentrate your will upon the desire that that needle remain in front of you, it remained. With the ebbing or dispersion of your will power it retreats.

"I have studied for many years upon this branch of telepathy. It may sound ridiculous to say telepathy, still it is true. I myself have very strong will, but it is not due to the machine, although I fancy that has been of no little benefit to me at times. It is certainly true that any person who will exercise his mind with this instrument day after day and day after day will strengthen his will. Strengthen his character? No, no, no. No machine can be made that will do anything like that. But it reflects the human emotions as nothing that was ever conceived before has done. It is as delicate as it is possible for a machine to be, and the more one studies it, the more one realizes the delicacy of his emotions."