Grant Brambel

From Kook Science

| Grant Brambel | |

|---|---|

Newspaper sketch of Brambel, 1896. | |

| Alias(es) | The Wizard of Sleepy Eye |

| Known for | "Brambel's Rotary Engine" |

Grant Brambel (or Bramble) was an railroad depot agent and telegraph operator in Sleepy Eye, Brown County, Minnesota, working for the Chicago North-Western line, who beginning in 1896 became the object of North American press interest over a miniature rotary engine he had invented and patented a year earlier, in some reports called a perpetual motion machine[DH] (though Brambel himself never made such assertions), for which he was, it was claimed, offered millions of dollars for the manufacturing rights. It was later discovered that none of the widely published reports were true, and Brambel's engine design was ultimately found to be inoperative and not capable of producing the energy alleged.[AM]

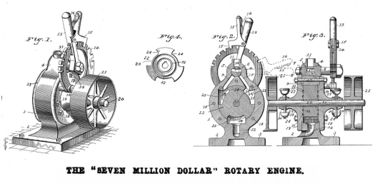

"Brambel's Rotary Engine" (U.S. Patent 550,582, 3 Dec. 1895)

- US550582. Rotary Motor. 3 Dec. 1895. "My invention relates to motors, and particularly to rotary engines having reversible concentric pistons; and the objects in view are to provide a machine of simple construction with means for causing the maximum expansion of steam, to provide an improved construction of piston whereby the force of expansion is economized, and, furthermore, to provide simple and efficient means for lubricating and packing the piston." https://patents.google.com/patent/US550582A/

Press Coverage

- SC (20 Nov. 1896), "Brambel's Valuable Patent", San Francisco Call (San Francisco, Cal.): 4, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85066387/1896-11-20/ed-1/seq-4/, "ST. PAUL, MINN., Nov. 19 — A representative of an English syndicate was in Sleepy Eye yesterday and offered Grant Bramble £10,000 more for the patent right of the Bramble rotary engine, patented by him, than was offered by the American syndicate. Bramble had just accepted the offer of £320,000 from the Allen syndicate and was forced to decline the offer of $50,000 more."

- "THE BRAMBEL ROTARY ENGINE", Scientific American 76 (5): 74-75, January 1897, https://archive.org/details/scientific-american-1897-01-30/page/n9

Last November the press of the country was informed by special telegrams that Mr. Grant Brambel, of Sleepy Eye, Minn., had invented and patented a rotary engine for which he was offered at that time £320,000 ($1,600,000) from an "English syndicate." It was reported that the whole amount of the purchase money was paid over in cash and deposited in Chicago banks by the inventor. There are a number of variations of the story, of which the following is an example, the clipping being taken from the Chicago Daily Tribune:

"The engine does away entirely with the crank motion of the steam engine, a most desirable, but to all intents and purposes an impossible thing to do. The engine uses its own plunger for a cutoff. The engine is steam tight, and requires no ring packing. It can be made marine type, and of course can be either simple or compound.

"It is not a cheap machine, although it costs very much less than an ordinary engine. Its weighs less and occupies only a fraction of the space of the old style engine. Mr. Brambel says: 'When anyone can build a fifty horse power engine that may be carried around in a hand satchel he has something that is very valuable, particularly when that engine is adapted to any and all kinds of work wherever power is used. The Brambel engine of fifty horse power, weighing less than a hundred pounds, may be attached to the end of the armature of a dynamo and all the belting done away with, or a Brambel engine not larger than a common saucer could be attached to a creamery separator, and set it whirling at the rate of 6,500 revolutions a minute. The largest of these engines, 250 horse power in size, is less than a foot wide at the base and eighteen inches high. It is in use in a dynamo room at Trenton, N. J., and the firm say they never had a more satisfactory machine. The patent was obtained a year ago, since which time several machines have been built and put into use.'"

The latest telegram that we have seen proceeds from Sleepy Eye, Minn., dated January 16, 1897. We quote from the New York Herald:

"The sale of Grant Brambel's rotary engine to the Allen syndicate, of London, England, has been consummated, and the Sleepy Eye inventor has letters of credit on the Bank of England for $6,700,000. The amounts paid were: For the English patent, $1,600,000; for France and Germany, $2,000,000; for the United States, $3,100,000.

"These amounts and the fact of the receipt of the letters of credit were verified by the inventor to-day when I called on him."

It is evident that the gentleman from Sleepy Eye is a very wide awake young person, and we take pleasure in publishing herewith an extract from his specification in which he describes the operation of the device. During the prosecution of the case some four patents were cited, one of which quite closely resembles the Brambel invention, and seems to depend upon the same general principle of operation. The extract reads as follows:

"What I claim is —

"In a rotary engine, the combination of a cylinder having opposite heads provided with registering extended bearing boxes, inwardly divergent steam inlet ports communicating with the interior cylinder at their inner ends and a common valve casing at their outer ends, a cutoff and reversing valve arranged in said casing, a rotary piston arranged in the cylinder and provided with peripheral pockets adapted to communicate with steam chambers at the inner ends of said ports, registering cross-sectionally semicircular grooves formed in the contiguous faces of the piston and cylinder heads concentric with said bearing boxes, said grooves combining to form cross-sectionally circular lubricating ducts, a shaft mounted in said bearings and fixed to the piston, and lubricating devices in communication with the bores of said bearings, whereby lubricating material is adapted to pass between the ends of the piston and the cylinder heads and accumulate in said lubricating ducts to form packing to prevent the exhaust of steam or the passage thereof from one pocket to another of the piston, substantially as specified."

It had not been our intention to describe or notice in any way the above mentioned invention, but we are in receipt of so many inquiries from correspondents and so many requests for copies of the patent that we have decided it was best to state the facts of the case and publish reproductions of the patent drawings and copy the salient features of the specification and the claim.

We have not written to Mr. Brambel for any light on the subject of his valuable patent. We learn, however, that he is a telegraph operator, and we imagine that possibly his vocation may have something to do with the wide publicity which the story has attained. We do not know what object there is in foisting upon the public a story which is in such a high degree improbable. We do not need to go beyond the patent itself and its very narrow claim to discover the falsity of the rumor. The principle upon which the engine is operated is by no means new, while the claim confines the design to minute details of construction. If, as it is claimed, an English syndicate has purchased the patent at a price of some $7,000,000, is it not likely that before investing so vast a sum the patent itself would have been submitted to rigid examination as to scope and validity? We believe, therefore, that the story can be regarded in no other light than a hoax, and it is the object of the Scientific American to try and arrive at the truth of such matters. We desire simply to direct the attention of anyone who may be sufficiently interested in the story to examine into the merits of the case, and we believe that they will be satisfied with us that the whole matter is founded on baseless rumor.

- SC (7 Jan. 1897), "INVENTOR BRAMBLE'S MILLONS - An English Syndicate Secures the Right to Make His Engines", San Francisco Call (San Francisco, Cal.): 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85066387/1897-01-07/ed-1/seq-3/, "SLEEPY EYE, Minn., Jan. 6. — Grant Bramble, who invented and patented the wonderful rotary engine, states that he has to-day transferred the right to manufacture and sell the engines to Henry Francis Allen, representing the Allen syndicate of England, for $3,100,000. This represents the sale for only the United States, England, Germany, France and Europe having been previously sold for $4,000,000. The inventor yet controls the rights for Mexico and the Canadian provinces. The inventor is now worth over $7,000,000 and does not appear in any way excited over the matter. He was yesterday elected as an Alderman of the village here."

- WDE (7 Jan. 1897), "HE'LL BE WORTH BILLIONS - Grant Bramble Will, by the Time He Has Sold the Earth", Wichita Daily Eagle (Wichita, Kan.): 3, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014635/1897-01-07/ed-1/seq-3/

- DH (13 Jan. 1897), "A MULTI-MILLIONAIRE NOW. Minnesota Backwoods Inventor of a Perpetual Motion Rotary Engine Sells His Patent.", Daily Herald (Brownsville, Tex.): 2, https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86089174/1897-01-13/ed-1/seq-2/

- AM (4 Feb. 1897), "'Sleepy Eye' Patent Examiners", American Machinist 20 (5): 94-26, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015080284568&view=1up&seq=162

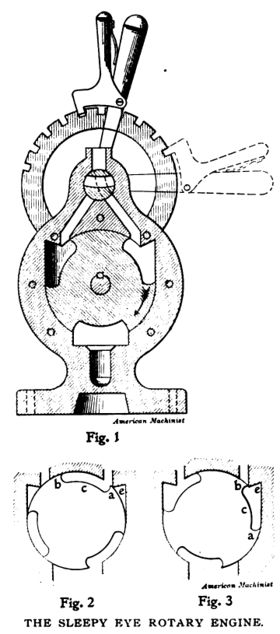

The notoriety attained by the Sleepy Eye rotary engine, on account of the announcement of its recent alleged sale by the inventor to a British syndicate for a fabulous sum, has led us to believe that we are warranted in calling the attention of our readers a little further to the matter. We have before us the specification and drawings of Grant Brambel's patent for rotary engine, issued December 3, 1895. There will be no difficulty in catch ing on to the idea of the invention.

In Fig. 1, which is reproduced from the patent drawing, the hand lever with the notched circular guide operates a three-way valve used as a throttle and reversing valve. When the lever and valve are in the position shown in the drawing, there is no admission of steam to the engine. When the lever is thrown over to the right, as indicated by the dotted lines, the steam is admitted to the right-hand passage, and it is asserted that the central piston and its shaft will then turn in the direction indicated by the arrow. If the lever were thrown over to the extreme left, it is asserted that the engine would run in the reverse direction. There can be no question that it would run equally well in either direction.

But would it run? If the piston were placed in the position shown in Fig. 2, it is just barely conceivable that if the throttle valve were opened quickly, the sudden in rush of steam striking against the face a might have a tendency to turn the piston in the desired direction. Anyone familiar with the operation of steam would know, however, that upon the admission of the steam the filling of the pocket a c b would be practically instantaneous; the pressure against a would be exactly equal to the pressure against b, and the rotative effect upon the one in one direction would be exactly balanced by the rotative effect against the other in the other direction. At the same time, the pressure of the steam upon the circular surface c would press the entire piston with great force against the opposite wall of the case, holding it as in a vise, and the piston could not possibly rotate. The simple fact is that a, let us say, "sleepy eye" patent office examiner allowed a patent for a rotary engine which is not a rotary engine at all, but an absolutely inoperative device.

Suppose that at this moment some intelligent inventor with a meritorious invention, and represented by an honest attorney, has an invention which he knows must be acted upon by this same examiner, what must be the feelings with which they must regard him?

The angular pocket e in the case is called an expansion chamber, and it is assumed that the expansion of the steam in this chamber operates to rotate the piston. The expansion might perhaps operate in that way, only there is no expansion. From the time when communication is opened between the pocket a b c in the piston and the "expansion chamber," which occurs just after the pis ton passes the position shown in Fig. 2, until communication is closed when the position of Fig. 3 is reached, there is no enlargement of the chamber, and consequently no expansion. The "sleepy eye" examiner, however, evidently did not see it.

As we said above that a patent office examiner had allowed a patent upon an inoperative device, it may be proper to qualify that a little. In addition to the essential features of the invention that we have referred to, there are others which need not be shown in detail, but which are embraced in the one comprehensive combination claim, and whose omission in the construction of the engine would involve a departure from the claim, and leave the invention entirely unprotected. If certain oil passages particularly specified in the claim were omitted or essentially changed in the construction, there would be absolutely nothing of the entire alleged invention which the claim would hold. The "sleepy eye" examiner, after all, did not allow "a worthless patent upon a worthless invention," for he practically allowed no patent, or protection, at all.

The issuance of such a patent as that of the Brambel rotary engine is only possible by the co-existence of an inventor, a patent agent and a patent office examiner, neither of whom is an ideal of his class. By putting it in this way we may avoid the use of all unpleasant adjectives and still convey our meaning. The use of adjectives is largely a matter of taste, and tastes differ.

And this patent, they say, was sold to a British syndicate for $7,100,000, with the rights for Mexico and Canada still undisposed of!

The latest and most reliable information in the matter is that Grant Brambel has not sold his engine. As he certainly has nothing salable, it is not easy to see how he could have sold anything.

- "A CHAPTER OF CURIOSITIES", Engineering News and American Railway Journal (New York) 38 (13): 200-201, 1 Apr. 1897, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.e0000401661&view=1up&seq=240

There has been long accumulating in the office of this journal a collection to which it is difficult to give a name. We sometimes call it “the crank drawer”; but “the wild-cat cage” would be, perhaps, a more appropriate name. This drawer contains letters, circulars, newspaper clippings, etc., regarding some of the inventions and schemes that are constantly being brought to our attention which are interesting, not because of their merit, but be cause of their absurdity.

As this number of Engineering News is published on the first day of April, it has seemed to us an appropriate time to give our readers a glimpse of the contents of this drawer, in the hope that they may share in the amusement which we have found in the collection.

Near the top of the pile we find a collection of clippings regarding what probably deserves the palm as the master hoax of 1896, "The Brambel Rotary Engine." In November last telegraph dispatches were sent out announcing that Grant Brambel, a telegraph operator of Sleepy Eye, Minn., had sold to an English syndicate a patent on a rotary steam engine for the sum of $1,600,000 in cash. This item was published in hundreds of dailies all over the country, including the most reputable and conservative journals. Immediately afterward other dispatches announced that the total selling price was $6,000,000, which was later changed to $7,100,000. Of course such an item was a bonanza to the representatives of the "New Journalism," and also to that class of papers which are conducted to boom patent procuring or patent selling agencies. Representatives of these journals descended on the village of Sleepy Eye, and secured the whole story of the invention from the inventor himself, with pictures galore, from the inventor's physiognomy to the seven by nine house in which he resides, and not forgetting the engine itself, which, in its newspaper portraits, resembled a fat coffee mill with a tumor on top.

So much publicity was given to the matter finally, that several Western newspapers of reputation sent representatives to investigate the matter, and our contemporary, “The American Machinist,” hunted up Brambel's rotary engine patent, and illustrated the engine with appropriate comments. The real facts of the case, as we gather from these investigations, were about as follows: Brambel did invent a rotary engine and obtained a patent upon it in 1895. The engine shown in this patent, is “far from the best and not far from the worst” of the many hundred rotary engines that have been invented, to quote with approval the “Machinist;” and the claim of the patent is one of the sort that covers everything and protects nothing. Brambel did build, in conjunction with one Prescott, a local machinist at Sleepy Eye, some sort of a rotary engine which was operated to drive the machinery in Prescott's shop. As for the story of the sale, from all the evidence collected, it appeared that an English “promoter" named H. F. Allan, who had been arrested for swindling in Minneapolis in 1891 and again in New York in 1894, was the “syndicate” to whom Brambel “sold” his patents. According to the Chicago “Tribune” Brambel created a similar sensation on a smaller scale at Skaneateles, N. Y., several years ago by announcing that he had sold a patent on an electric lamp for $70,000. But the evidence of his receipt of that sum was as evanescent as is the evidence of his receipt of the $7,000,000, more or less, from the “Allan syndicate.” According to latest reports Mr. Brambel still continues to labor as a telegraph operator, and to live upon the salary which he derives from this work, in heroic disregard of the millions which he claims are lying to his credit in the banks of Chicago, London and other cities. The village of Sleepy Eye has returned to its somnolent condition, and the representatives of the New Journalism are after some other hoax.

One amusing episode of the affair is told with highly appropriate comments in the following extract from the New York “Times”:

Grant Brambel, the telegraph operator at Sleepy Eye, Minn., who claims to have invented a rotary steam engine of remarkable, not to say supernatural, efficiency, and to have sold it to an English syndicate for millions more or less numerous, has taken offense at the incredulity with which his yarns have been received. Moved by this feeling he has caused the following savage menace to be printed in the advertising columns of one of the village papers:

“To all concerned: Our personal matters that are so much talked about must cease at once, or it will be placed in proper hands of the law.”

As among the “all concerned,” having expressed reluctance from the very beginning to number Mr. Brambel among the world's great inventors, we have naturally read this notice with grave attention, and it is only fair to confess that it has changed our opinion of him materially. The man ungenerous enough to write English so unlike that in common use may well have constructed a motor that ignores the laws of physics. The Wizard of Sleepy Eye has vindicated conclusively his right to be considered an original thinker; that is, he thinks spirally. Probably his engine works in the same way, and, owing to that peculiarity, has wormed itself off somewhere into the fourth dimension, out of sight of the impertinent machinists who spend their time in deriding it and its inventor.

- MT (19 Apr. 1897), "Two Fakes at Sleepy Eye", Indianapolis Journal: 2, https://newspapers.library.in.gov/cgi-bin/indiana?a=d&d=IJ18970419.1.2&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-%22Grant+Bramble%22+%22Sleepy+Eye%22------, "The air ship is said to have been seen hovering over Sleepy Eye. Perhaps it was negotiating for one of Grant Bramble's rotary engines."

Reading

- Museum Lady (May 2013), Grant Bramble Invention Hoax, thedepotlady.blogspot.com, https://thedepotlady.blogspot.com/2013/05/grant-bramble-invention-hoax.html