George Psalmanazar

From Kook Science

George Psalmanazar [Psalmanaazaar] (c. 1679 - May 3, 1763) was an apparently French-born writer who engaged in the pretense of being a native of Formosa, becoming a celebrity in England for a brief time before being ultimately compelled to admit his fraud, thereafter withdrawing from public life to become an editor, essayist, pamphleteer, and writer-for-hire on London's Grub Street.

Selected Bibliography

- Psalmanaazaar, George; Oswald (trans.) (1704), An Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa, an Island Subject to the Emperor of Japan: Giving an Account of the Religion, Customs, Manners, &c., of the Inhabitants. Together With a Relation of What Happened to the Author in His Travels; Particularly His Conferences With the Jesuits, and Others, in Several Parts of Europe. Also the History and Reasons of His Conversion to Christianity, With His Objections Against It (in Defence of Paganism) and Their Answers. (1st ed.), London: Printed for Dan. Brown, at the Black Swan without Temple-Bar; G. Strahan, and W. Davis, in Cornhill; and Fran. Coggin, in the Inner-Temple-Lane

- P--n--r, G. (1707), A Dialogue Between a Japonese and a Formosan, About Some Points of the Religion of the Time, London: Bernard Lintott, Nando's Coffee House

- Psalmanazar, George (1764), Memoirs of ****, Commonly Known by the Name of George Psalmanazar; a Reputed Native of Formosa. Written by Himself in Order to be Published after his Death., London: Printed for the Executrix, https://archive.org/details/dli.granth.72226

Resources

Reading

- Rees, Abraham, ed. (1819), "PSALMANAZAR, George.", The Cyclopaedia; Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences and Literature, 28

PSALMZANAZAR, George, in Biography, a literary impostor who assumed that name, was probably a native of the fourth of France, though he never made known either his country or family. He was supposed to be born about 1680, and educated partly at a Franciscan seminary, then at a Jesuits college, and at last at a university. He seemed to have had an uncommon facility in the attainment of languages, but was not sufficiently steady to render himself tolerably perfect in any. At an early age he left the college, in order to support himself by private tuition. But this was not at all agreeable to his disposition, and he went to Avignon, where he pretended to have left his father's house on account of an ill usage through his attachment to the Roman Catholic religion. He next assumed the character of a young Irish student of theology, who had left his country for the sake of religion, and was going on a pilgrimage to Rome; and having obtained a certificate, and equipped himself with a suitable garb, he set out on his rambles. After passing through several scenes he enlisted for a soldier, and become acquainted with one Innes, a chaplain to a Scotch regiment. This man soon discovered Psalmanazar to be an impostor, but instead of exposing him, immediately conceived a plan of more extensive fraud, by which he himself might reap some profit. He engaged the young man to act the part of a convert from heathenism, and having written a letter to Dr. Compton, bishop of London, with a flattering account of his pupil, he baptized him in a public manner, procured his discharge, and in consequence of the bishop's invitation, proceeded with him to London. The learned prelate listened to his story, which he endeavoured to pass for a native of the island of Formosa, of which little was known to Europeans. Innes set him about translating the church catechism into a pretended Formosan language, which he had framed, and he next employed him in writing a "History of Formosa." Though he had no other materials than what his own invention could furnish, aided by the account of Formosa by Varenius, he drew up such a work as excited the curiosity of the public and was regarded, at that time, as containing genuine information; though in fact, when examined with a careful and scrutinizing eye, it was found full of inconsistencies and improbabilities. A second edition was preparing, when the bishop of London sent Psalmanazar to Oxford to pursue his studies in that seminary. He remained there six months, and then returned to London, but either his patrons distrusted him, or failed to put him in any suitable way of living, for in a few years he sold his name to a manufacturer of a kind of white porcelain, which was to pass as a secret communicated by Psalmanazar, and was advertised by the name of the "curious white Formosan work." He next endeavoured to get some money as a medical empiric, and as a teacher of languages and fortification; but these resources were inadequate to his wants, and he became a clerk to a regiment of dragoons, which marched to the north in the year 1715, and in that character he visited many parts of the kingdom. Without following him through all the changes of this part of his life, it may be observed that he acknowledges himself to have been dissolute, unprincipled, and void of any fixed purpose. At length he obtained some steady employment as a translator, and is said, that Law's Serious Call, without other devotional works falling into his hands, he was awakened to a sense of his past misconduct, and formed resolutions of amendment. He entered deeply into the study of the scriptures, and of the Hebrew language, in which he soon acquired such a proficiency that he composed a dramatic piece in Hebrew verse, entitled "David and Michael." His reputation for learning caused him to be engaged as one of the writers in the Universal History, which was his principal literary labour, and employed much of his time. The history of the Jews, the Celtes, and Scythians, of the Greeks at the early periods, the ancient Spaniards, Gauls, and Germans, were the chief parts of which he contributed to this voluminous work. It does not appear when he dropt the imposture of being a Formosan convert; but in his last will, dated 1752, there is an explicit and penitential confession of his criminality in adopting that fraud, and supporting it by his pretended account of the island. After his death, in 1763, his life, written by himself, was published, from which farther information may be obtained. See Memoirs f the Life of **** commonly known by the name of George Psalmanazar.

- "George Psalmanazar", Book-Lore: A Monthly Magazine of Bibliography 6 (33): 71-78, August 1887, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044083143206&view=1up&seq=95

GEORGE PSALMANAZAR, or Psalmanaazaar, as he called himself when posing as a "Japponese," was a person of very consider able learning and vast ingenuity. The secret of his birthplace, name, and parentage has never been penetrated, and the little knowledge we possess is entirely derived from what he chooses to relate in his Memoirs, a posthumous work to which we shall have occasion shortly to refer.

Psalmanazar was, according to his own account, born in France in the year 1679, and educated in an archiepiscopal city by the Jesuits. The name of the city and of the college are unknown. When quite a boy he could speak Latin fluently, and had acquired a firm grasp of those principles of grammatical construction which afterwards served him in such stead when he came to concoct a language for himself wherewith to deceive the Bishop of London and other learned divines of the age.

With the advantage of a sound education in his favour, he left his preceptors the Jesuits, and started life as a tutor, and then speedily fell into rambling ways, and became involved in poverty and disappointment. Finding that the narrow road, combined with a temperate and sober life, might be as good in theory as he soon discovered it to be difficult to follow in practice, he decided to become a sufferer for religion's sake; and having procured a certificate that he was of Irish extraction, and a declaration vouched for by several persons of position that he had left that country for the sake of the Catholic faith, he started for Rome on a pilgrimage.

In those days it was customary for the devout who journeyed towards the Eternal City to go arrayed in a pilgrim's garb, and to carry an oaken staff in their hands. Psalmanazar, whose chief object was deception, commenced his career well by stealing what his wardrobe was deficient in, for happening to enter a chapel dedicated to a miraculous saint, he stripped the walls of a serviceable staff and cloak, and begged his way in fluent Latin, accosting the clergy and persons of figure whom he met. So generous and credulous did he find them that, as he admits to his own disadvantage, he might easily have saved money had not the old leaven in his composition asserted itself. An ale-house had more charm for Psalmanazar than St. Peter's, and before he had accomplished the first twenty miles of his pilgrimage he was irresistibly attracted to an inn, where, his sober suit discarded, he squandered a considerable portion of his time and the whole of his money.

Things now became critical, but Psalmanazar was not the man to despair. Having heard the Jesuits speak much of China and Japan, he formulated a scheme which, for rashness, has perhaps been unequalled in the history of the literary world. Leaving the ale-house and once more assuming the pilgrim's garb, he travelled into Germany, and when there, well out of the way, so to speak, of anyone who would be at all likely to recognise him, he gave out that he was a native of Formosa, a convert to Christianity, travelling for instruction. To bolster up this deception he formed a new language and character on grammatical principles, which he wrote from right to left, after the manner of Oriental scribes. He planned a new religion, based chiefly upon a belief in the transmigration of souls, and, in short, built up a fabric of falsehood and fraud which, had it been possible, would have deceived the very elect. Then he joined the Dutch army, and altered his plan so far as to declare himself an unconverted heathen, and at Sluys was introduced to the Chaplain of the Forces, who brought him over to England and presented him to the Bishop of London. The patronage he obtained in this quarter procured him a large circle of friends, who extolled him as a prodigy; and on Dr. Halley and others expressing doubts on the genuineness of his pretensions, they were themselves silenced by the voice of popular opinion. Then, as now, religion was frequently stretched until it engendered hysteria, and everyone who wished to pose as a humanitarian vied with his neighbour in attempting to bring the stranger to a knowledge of the Christian religion.

How this same stranger, barely twenty years of age, must have laughed at his arch-dupe the Lord Bishop of London and his crowd of satellites, who got their guest to translate the Church Catechism from Latin into Formosan, and pronounced the translation, though they could not read a word of it, to be very good; so good, in fact, that they next besought him to write a history of his native island and publish it for the benefit of the world.

This Psalmanazar did in the space of two months, and though he had, of course, never been in the island in his life, or indeed in any Oriental country, he succeeded in producing a history which, had he kept clear of exaggeration, might perhaps have been quoted at the present day as an authority.

Formosa was then, as now, an island of which very little is known, and the author of the history could therefore say pretty much what he pleased. The conversation of the Jesuits in the old days, a few books, including Candidus on the Isle of Formosa, and Varenius's History of Japan, together with a first-rate imaginative power, and the work was practically mapped out, written in Latin, translated by an assistant engaged at the expense of the Bishop, and published to the gaping mob, who devoured a first edition in less than a week, and called out for more.

Psalmanazar, the converted Formosan, was now the lion of the town, and, being treated as the protégé of the Bishop of London, revelled in luxury and every thing that tends to make life happy. Then at last he fell, not indeed suddenly, as most lions do, but little by little, until he was metamorphosed into a commonplace and, wonderful to relate, honest man.

The cause of the downfall was this. Psalmanazar, in the course of his description of the island, states that the god, a sort of Typhon, demanded sacrifices upon a gigantic scale. No less than 18,000 male children were accordingly sacrificed every year, which in an island so small would have speedily depopulated it. This lie was, indeed, gratefully digested by most who read the book; but one or two, upon whose credulity a severe strain had been put, refused to accept this statement without investigation. Psalmanazar, on being appealed to, confirmed the assertion; he could not safely deny it, for it appears he had once inadvertently said the same thing at a distinguished gathering of admirers. He therefore boldly adhered to what he had previously stated, explaining that the children were imported, bred on purpose, and so forth.

Society was now divided in opinion upon the important question whether or no Psalmanazar was an impostor; and as evidence of the extreme tenacity with which many people adhere to an opinion, surely none can be greater than a book which was published about this time, bearing a dedication to the Bishop of London as follows:

"May it please your Lordship. Since your commands brought George Psalmanaazaar into England, we humbly presume to lay before you these inquiries into the objections against him, and humbly pray your Lordship's judgment of them, to which we shall entirely submit."

This book is "An Enquiry into certain objections against George Psalmanazar of Formosa, in which the accounts of the people and Language of Formosa, by Candidus, and the other European authors, and the letters about Psalmanazar are proved not to contradict his accounts, with Maps of Formosa and Islands adjacent, to which is added Psalmanazar's answer to M. D'Amalvy, of Sloice. London, printed for Bernard Lintott, in Fleet Street."

The map which is prefixed is copied, so an inscription states, from one that was brought from the East Indies by Captain Bowery, the author of the Mallayo Grammar and Dictionary.

The objections urged against Psalmanazar and his history are numerous, these are answered or evaded in the book. The chief are as follows:

"Q. Were you not formerly a Roman Catholic, and a Novice among the Jesuits, ejected upon account of ill Morals?

"A. The Querist either believes Psalmanazar or not; if the first, Psalmanazar has already affirmed the Contrary; if the latter, why does he ask him any question at all?

"Q. Is it not a Rarity that an Indian should become a member of the Church of England?

"A. We do not think this question at all to the purpose, but rather against the querist, for if it was no rarity to convert a Japponese to our church, then the wonder about Psalmanazar ceases.

"Q. How a stripling att the Age of 18 or 19 (much time being spent in rambling) could attain to such great a Perfection in the Lattin Tongue, as to write the natural and politick History of a Country in that Language?

"A. It must be recollected that Psalmanazar learnt the Latin Tongue at Formosa for Practice, and the reason of the thing tells us he must learn it by having the natural and politick History of his own Country taught him in Latin, for his Tutor did not bring his Books with him.

"Q. There is a Grammar of the Japan Language in Town, from whence some words have been transcribed and shewn Psalmanazar, but he knew nothing of them; how comes it that though he says his Language is a Dialect of the Japan he knows nothing whatever of it?

“A. We find the Japan Language has dialects not very intelligible to the Natives themselves, by the account given by Varenius of it out of Maffeus, Sermo Japponensium unus &c. There is one common Language of all Japan, but so different and manifold, that they may be very well accounted many, there being many ways of expressing the same things.

"Q. How comes it that there is a great deal of Greek in Psalmanazar's Formosan language?

"A. We find a short Sentence of Japonese in Varenius with but six words, and one of them both sounds and signifies like Greek. Var., Ch. 1., de Relig. in Jap.

"Q. If Psalmanazar is a Japanese, as he says he is, should not his hair be black, his face yellow or olive or Tawny, his Mien a little more diverse, to denote him such a stranger as he pretends?

"A. In all places there are some who are contrary to the general Colour & c. of the Country. Some fair in Afric, some black in England. As to his hair, we know not what Influence the Climate he is now in may have upon the Colour of that."

Notwithstanding that these answers and others like them, formulated by the anonymous authors of the Enquiry, were adjudged to be satisfactory by a large number of people, the investigation still continued, and one fine morning, in the very midst of the furious literary war, Psalmanazar confessed the fraud, and so, ceasing to be an object of interest, he disappeared from the drawing-rooms of the great, though not from the world. The remainder of the life of this extraordinary man was spent in writing, which procured him a comfortable support. He was concerned in several works of positive credit, among them being The Universal History, published in 1747, and the Essay on Miracles. We are even assured that he lived irreproachably for many years, and died in the odour of sanctity in 1763. The History of Formosa, which is a fairly scarce book, is collated as follows:

"An | Historical and Geographical | Description | of | Formosa | an | Island subject to the Emperor of Japan | giving | An account of the Religion, customs | Manners, & c. of the inhabitants. Together with a Relation of what happen'd to the Author in his Travels; particularly his Conferences with the Jesuits, and others, in several | Parts of Europe. Also the History and Reasons of his Conversion to Christianity with his | Objections against it ( in defence of Paganism and their answers | To which is prefixed | A preface in vindication of himself from | the Reflections of a Jesuit lately come from China | with an account of what passed between them | By George Psalmanaazaar | a Native of the said Island, now in London. Illustrated with several cuts. London | Printed for Dan Brown at the Black Swan without Temple | Bar; G. Strahan and W. Davis in Cornhill, and Fran. | Coggan in the Inner-Temple Lane, 1704."

Dedication to the Bishop of London, 5 pp. Preface, 14 pp. Errata, 1 leaf. An account of the travels, etc., pp. 327. Appendix at the end, but paged 128, 129, 130, and 131. Contents, 5 pp. Plates : ( a ) Exterior of a temple, to face p. 173; ( b ) tabernacle and altar, to face p. 174; ( c ) altars, to face p. 194; ( d ) folding plate, "The funeral or way of burning the dead bodies," to face p. 206; ( e ) costumes, to face p. 229 and 230 ( 3 plates ); ( f ) "The Vice Roys Castle," to face p. 233; ( g ) the Formosan alphabet, folding plate, to face p. 271; ( g ) two plates of ships, to face p. 276; ( h ) figures of money, to face p. 278.

This extraordinary book goes fully into details of the form of government of Formosa, the religion, fast-days, marriage ceremonies, the opinion concerning the state of the soul after death, manners and customs, weights and measures, clothes, fruits, animals, money, arms and musical instruments, and even describes the appearance of the Viceroy of Formosa and his splendid retinue. With regard to the zoological aspect of the island, Pzalmanazar observes:

Generally speaking, all the animals which breed here are to be found in Formosa; but there are many others there which do not breed here, as Elephants Rhinocerots, Camels, Sea-Horses, all which are tame and very useful for the service of man. But they have other wild beasts there, which are not bred here, as Lyons, Boars, Wolves, Leopards, Apes, Tygers, Crocodiles, and there are also wild Bulls, which are more fierce than any Lyon or Boar, which the natives believe to be the Souls of some Sinners undergoing a great Penance. But they know nothing of Dragons or Land Unicorns, only they have a Fish that has one Horn. And they never saw any Griphons, which they believe to be rather fictions of the Brain than real Creatures."

Modern acquaintance with the island and its peculiarities discloses the fact that although the Formosan fauna have even yet been but partially ascertained, and although there may consequently be elephants and rhinoceroses, camels, tigers and crocodiles there, there are, as a fact, only known to be three kinds of deer; wild boars, bears, goats, monkeys, squirrels, and flying bats in abundance, and panthers and wild cats in lesser numbers. As to the inhabitants — the Chinese and such of the aborigines who have adopted Chinese manners and customs apart — they are well known to be the most bloodthirsty savages on the face of the earth, without any manners and customs worth narrating, who do neither weigh nor measure, and have no notion of divinity, nor any faith in marriage customs, nor law. These are the people who, according to Psalma nazar, were experts in the doctrine of transmigration, who could recite the Lord's Prayer, commencing "Amy Pornio dan chin Ornio viey," and ending "Amien," to say nothing of the Apostles ' Creed and Ten Commandments. The wonder is not that so palpable a fraud should have deceived so many, but that anyone with common-sense could have been deceived at all.

As we have said, Psalmanazar spent the remainder of his life in an endeavour to make an honest living, and he succeeded. That he repented of the fraud he had practised on a confiding public, there is also every reason to believe, for in his Memoirs, published after his death, by his executrix, he lays bare and openly confesses the villainies which he had committed in his youth. This work, which was delivered to subscribers on the 10th of September, 1764, is entitled shortly "Memoirs of **** commonly known by the name of George Psalmanazar, a reputed native of Formosa, written by himself in order to be published after his death, being an account of his Education, Travels, Adventures, Connections, Literary Productions, and pretended Conversion from Heathenism to Christianity; which last proved the occasion of his being brought over into this Kingdom, and passing for a Proselyte, and a member of the Church of England.”

As stated, the design of leaving the Memoirs was to undeceive the world with respect to the account Psalmanazar gave of himself and of the Island of Formosa, and this good resolve is ascribed by the author in his preface " to the religious education I had happily received during my tender years."

Psalmanazar concealed his name and parentage, for as he says, "I hope I shall be excused from giving an account either of my real country or family, or anything that might cast a reflection upon either, it being but too common though unjust to censure them for the crimes of private persons, for which reason I think myself obliged, out of respect to them, to conceal both."

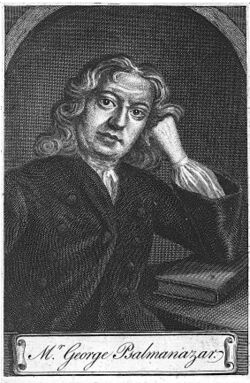

Such is the short and necessarily imperfect account of one of the greatest impositions that was ever foisted upon the public. When we come to read the History of Formosa and to weigh the many extraordinary statements that are made so casually throughout the book, it seems absolutely incredible that anyone could have believed for a single moment in George Psalmanazar, whose very likeness prefixed to his book should have been sufficient to condemn him.

The following extract from the will of this remarkable man is useful as throwing some little light upon the Memoirs, and the circumstances and professions — true or false — which prompted him to write them:

"Part of the last will and Testament of me, a poor sinful and worthless Creature, commonly known by the assumed name of George Psalmanazar. desire that my body when or wherever I die may be kept so long above ground as decency or conveniency will permit, and afterwards conveyed to the common burying ground and there interred in some obscure corner of it without any further ceremony or formality than is used to the bodies of the deceased pensioners, where I happen to die and about the same time of the day, and that the whole may be performed in the lowest and cheapest manner. And it is my earnest request that my body be not enclosed in any kind of coffin, but only decently laid in what is called a shell, of the lowest value, and without lid or other covering which may hinder the natural earth from covering it all around.

"The Books relating to the Universal History, and belonging to the proprietors, are to be returned to them according to the true list of them, which will be found in a blue paper in my account Book; all the rest being my own property, together with all my household goods, wearing apparel, and whatever money shall be found due to me after my decease, I give and bequeath to my friend Sarah Rewalling, together with such manuscripts as I had written at different times, and designed to be made public if they shall be deemed worthy of it, they consisting of sundry essays on some difficult part of the Old Testament, and chiefly written for the use of a young clergyman in the country, and so unhappily acquainted with that kind of learning that he was likely to become the butt of his sceptical Parishoners, but being, by this means, furnished with proper materials, was enabled to turn the tables upon them.

"But the principal manuscript I thought myself in duty bound to leave behind is a faithful narration of my education and the follies of my wretched youthful years, and the various ways by which I was in some measure unavoidably led into the base and shameful imposture of passing upon the world for a native of Formosa, and a convert of Christianity and backing it with a fictitious account of that Island, and of my own travels, conversion, etc., all or most of it hatched in my own brain without regard to truth or honesty. It is true I have long since disclaimed even publikely all but the shame and guilt of that vile imposition, yet as long as I knew there were still two editions of that scandalous romance remaining in England, besides the several versions it had abroad, I thought it incumbent on me to undeceive the world by unravelling that whole mystery of iniquity in a posthumous work which would be less liable to suspicion as the author would be far out of the influence of any sinister motives that might induce him to deviate from the truth. The whole of the account contains 14 pages of preface and about 93 more of the second relation written in my own hand with a proper title, and will be found in the deep drawer on the right hand of my white cabinet. However, if the obscurity I have lived in during such a series of years should make it needless to revive a thing in all likelihood so long since forgot, I cannot but wish that so much of it was published in some weekly paper, as might inform the world, especially those who have still by them the above-mentioned fabulous account of the Island of Formosa, etc., that I have long since owned, both in conversation and in print, that it was no other than a meer forgery of my own devising, a scandalous imposition on the public." The will bears date the 23rd April, 1752, old style.

- Keevak, Michael (2004), The Pretended Asian: George Psalmanazar's Eighteenth-Century Formosan Hoax, Detroit: Wayne State University Press