Bohun Upas, the Poison Tree of Java

From Kook Science

Bohun (or bohon) upas (from the Malay: pohon upas, "poison tree") is a cryptobotanical tree described as being native to the island of Java in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, which, according to a fantastical story attributed to N. P. Foersch, produced toxic vapours that made the surrounding environment uninhabitable for miles in any direction but was highly sought after in the 1770s as the source of a highly poisonous gum that was harvested by condemned prisoners for the local Javanese Emperor, Susuhunan Pakubuwono III. While Foersch's story was generally discredited, it was taken up as a popular literary instrument, appearing in the poems of Erasmus Darwin, Robert Southey, Lord Byron, and others.

The term upas is a Javanese-Malay term meaning "poison," and refers to arrow and dart poison harvested from the antiaris tree (antiaris toxicaria), which is widely distributed across Southeast Asia, Oceania, and Australia, and does not produce the toxic effects on the surrounding environment that is attributed to the legendary bohun upas.

Dramatis Personae

From the 1783 story, we find the players are:

- N. P. (or J. N.) Foersch, a Dutch surgeon who was resident in the Dutch East Indies - identified by John Bastin in his paper New Light on J. N. Foersch and the Celebrated Poison Tree of Java (Jour. Malay. of Royal Asiatic Society, 58.2, 1985) as likely to have been John Nichols Foersch, a German-born surgeon's mate who served aboard His Majesty's Ship Powerful;

- Mr. Heydinger, the translator of the Dutch text, described as a "German bookseller" near Temple Bar, London;

- Engelbert Kaempfer (Kempfer), a German naturalist who spent time in Java while travelling through Asia, known for his book Amoenitates Exoticae (1712);

- Petrus Albertus van der Parra, Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies (1761-1775);

- an unnamed Muslim priest, who served to prepare the condemned prior to their attempt to harvest the poison tree;

- an unnamed Emperor, likely Pakubuwono III, Susuhunan of Surakarta;

- an unnamed Sultan, likely Hamengkubuwono I, Sultan of Yogyakarta;

- an unnamed Massay, possibly Mangkunegara I of Mangkunegaran;

- and several unnamed rebels and condemned prisoners, victims of the poison tree.

The Story

Natural History of the Poison-Tree in Java (London Magazine, Dec. 1783)

- "NATURAL HISTORY OF THE POISON-TREE IN JAVA.", The London Magazine, or Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer 1: 511-517, December 1783, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015013157279&view=1up&seq=537

THE following description of the BOHON UPAS, or POISON-TREE, which grows on the island of Java, and renders it unwholesome by its noxious vapours, has been procured for the London Magazine, from Mr. Heydinger [formerly a German bookseller near Temple-Bar], who was employed to translate it from the original Dutch, by the author, Mr. Foersch, who, we are informed, is at present abroad, in the capacity of surgeon on board an English vessel.

This account, we must allow, appears so marvellous, that even the Credulous might be staggered. The readers of this narrative will probably think of the celebrated Psalmanazar, and his equally famous History of the Island of Formosa. But this narrative certainly merits attention and belief. The degree of credibility which is due to the several circumstances rests with Mr. Foersch. With regard to the principal parts of the relation, there can be no doubt. The existence of the tree, and the noxious powers of its gums and vapours, are certain. For the story of the thirteen concubines, however, we should not choose to be responsible.

Travellers and naturalists have mentioned trees of the same destructive nature in other places, and particularly, if we are not mistaken, in some parts of South America. This very Bohon-Upas is mentioned by the learned Kemptser, but its situation, its nature, and its destructive qualities, have never been so clearly, so fully, or so philosophically described, as by the author of the following description.

It may probably be asked, why no efforts have been made to destroy so dreadful a tree? — more dreadful, indeed, in effects, than the union of plague, pestilence, and famine. The reasons are obvious. No man could venture to remain near it for so long a space of time as would be requisite to cut down a tree of such magnitude; nor could materials set it on fire be carried to the place without almost certain destruction. But of all the arguments, the most forcible probably is, that the Emperor derives a very considerable revenue from the gum which is distilled from the Bohon-Upas. The auri sacra fames! the rage for possessing riches, is too powerful to be withstood, even in the most cultivated ages, and among the most polished nations! What then can be expected from an inhabitant of Java, and that man an Emperor! Who, like Achilles,

"Jura neget sibi nata, nihil non arroget armes!"

DESCRIPTION OF THE POISON-TREE, IN THE ISLAND OF JAVA,

BY N. P. FOERSCH.

TRANSLATED FROM THE ORIGINAL DUTCH, BY MR. HEYDINGER.THIS destructive tree is called in the Malayan language, BOHON-UPAS, and has been described by naturalists. But their accounts have been so tinctured with the marvellous, that the whole narration has been supposed to be an ingenious fiction by the generality of readers. Nor is this in the least degree surprising, when the circumstances which we shall faithfully relate in this description are considered.

I must acknowledge, that I long doubted the existence of this tree, until a stricter enquiry convinced me of my error. I shall now only relate simple, unadorned facts, of which I have been an eye-witness. My readers may depend on the fidelity of this account. In the year 1774, I was stationed at Batavia, as a surgeon in the service of the Dutch East-India Company. During my residence there I received several different accounts of the Bohon-Upas, and the violent effects of its poison. They all then seemed incredible to me, but raised my curiosity in so high a degree, that I resolved to investigate this subject thoroughly, and to trust only to my own observations. In consequence of this resolution, I applied to the Governor-General, Mr. Petrus Albertus van der Parra, for a pass to travel through the country. My request was granted, and having procured every information, I set out on my expedition. I had procured a recommendation from an old Malayan priest to another priest, who lives on the nearest inhabitable spot to the tree, which is about fifteen or sixteen miles distant. The letter proved of great service to me in my undertaking, as that priest is appointed by the Emperor to reside there, in order to prepare for eternity the souls of those who for different crimes are sentences to approach the tree, and to procure the poison.

The Bohon-Upas is situated in the island of Java, about twenty-seven leagues from Batavia, fourteen from Soura-Charta, the seat of the Emperor, and between eighteen and twenty leagues from Tiukjoe, the present residence of the Sultan of Java. It is surrounded on all sides by a circle of high hills and mountains, and the country round it, to the distance of ten or twelve miles from the tree, is entirely barren. Not a tree, not a shrub, nor even the least plant or grass is to be seen. I have made the tour all around this dangerous spot, at about eighteen miles distant from the center, and I found the aspect of the country on all sides equally dreary. The easiest ascent of the hills, is from that part where the old ecclesiastic dwells. From his house the criminals are sent for the poison, into which the points of all warlike instruments are dipped. It is of high value, and produces a considerable revenue to the Emperor.

ACCOUNT OF THE MANNER IN WHICH THE POISON IS PROCURED.

THE POISON which is procured from this tree, is a gum that issues out between the bark and the tree itself, like the camphor. Malefactors, who for their crimes are sentences to die, are the only persons who fetch the poison; and this is the only chance they have of saving their lives. After sentence is pronounced upon them by the judge, they are asked in court, whether they will die by the hands of the executioner, or whether they will go to the Upas tree for a box of poison? They commonly prefer the latter proposal, as there is not only some chance of preserving their lives, but also a certainty, in case of their safe return, that a provision will be made for them in future, by the Emperor. They are also permitted to ask a favour from the Emperor, which is generally of a trifling nature, and commonly granted. They are then provided with a silver or tortoiseshell box, in which they are to put the poisonous gum, and they are properly instructed how to proceed while they are upon their dangerous expedition. Among other particulars, they are always told to attend to the direction of the winds; as they are to go towards the tree before the wind, so that the effluvia from the tree are always blown from them. They are told, likewise, to travel with the utmost dispatch, as that is the only method of insuring a safe return. They are afterwards sent to the house of the old priest, to which place they are commonly attended by their friends and relations. Here they generally remain some days, in expectation of a favourable breeze. During that time, the ecclesiastic prepares them for their future fate by prayers and admonitions.

When the hour of their departure arrives, the priest puts them on a long leather cap with two glasses before their eyes, which comes down as far as their breast, and also provides them with a pair of leather gloves. They are then conducted by the priest, and their friends and relations, about two miles on their journey. Here the priest repeats his instructions, and tells them where they are to look for the tree. He shews them a hill, which they are told to ascend; and that on the other side they will find a rivulet, which they are to follow, and which will conduct them directly to the Upas. They now take leave of each other, and amidst prayers for their success, the delinquents hasten away.

The worthy old ecclesiastic has assured me, that during his residence there, for upwards of thirty years, he has dismissed above seven hundred criminals in the manner which I have described; and that scarcely two out of twenty have returned. He shewed me a catalogue of all the unhappy sufferers, with the date of their departure from his house annexed, and the list of the offences for which they had been condemned. To which was added the names of those who had returned in safety. I afterwards saw another list of these culprits, at the gaol-keeper's at Soura Charta, and found that they perfectly corresponded with each other, and with the different information which I afterwards obtained.

I was present at some of those melancholy ceremonies, and desired different delinquents to bring with them some pieces of the wood, or a small branch, or some leaves of this wonderful tree. I have also given them silk cords, desiring them to measure its thickness. I never could procure more than two dry leaves, that were picked up by one of them on his return; and all I could learn from him concerning the tree itself, was, that it stood on the border of a rivulet, as described by the old priest, that it was of a middling size, that five or six young trees of the same kind stood close by it; but that no other shrub or plant could be seen near it; and that the ground was of a brownish sand, full of stones, almost impracticable for travelling, and covered with dead bodies. After many conversations with the old Malayan priest, I questioned him about the first discovery, and asked his opinion of this dangerous tree, upon which he gave me the following answer in his own language:

"Ditalm kita ponjoe Alcoran Baron Suda tulus touloe Seratus an Soeda jlang orang Soeda Dengal disenna orang jahat di Soeda main Same Die punje pinatang prgidoe kita pegi Sam prambuange."

Which may be thus translated:

"We are told in our New Alcoran that, above an hundred years ago, the country around the tree was inhabited by a people strongly addicted to the sins of Sodom and Gomorrha. When the great prophet Mahomet determined not to suffer them to lead such detestable lives any longer, he applied to God to punish them; upon which God caused this tree to grow out of the earth, which destroyed them all, and rendered the country for ever uninhabitable."

Such was the Malayan's opinion. I shall not attempt a comment, but must observe, that all the Malayans consider this tree as an holy instrument of the great prophet to punish the sins of mankind, and, therefore, to die of the poison of the Upas is generally considered among them as an honourable death. For that reason I also observed, that the delinquents, who were going to the tree, were generally dressed in their best apparel.

This, however, is certain, though it may appear incredible, that from fifteen to eighteen miles round this tree, not only no human creature can exists; but that, in the space of ground, no living animal fo any kind has ever been discovered. I have also been assured by several persons of veracity, that there are no fish in the waters, nor has any rat, mouse, or any other vermin been seen ther; and when any birds fly so near this tree, that the effluvia reaches them, they fall a sacrifice to the effects of the poison. This circumstance has been ascertained by different delinquents, who, in their return, have seen the birds drop down, and have picked them up dead, and brought them back to the old ecclesiastic.

I will here mention an instance which proves this a fact beyond all doubt, and which happened during my stay at Java.

In the year 1775 a rebellion broke out among the subjects of the Massay, a sovereign prince, whose dignity is nearly equal to that of the Emperor. They refused to pay a duty imposed upon them by their sovereign, whom they openly opposed. The Massay sent a body of a thousand troops to disperse the rebels, and to drive them, with their families, out of his dominions. Thus four hundred families, consisting of above sixteen hundred souls, were obliged to leave their native country. Neither the Emperor nor the Sultan would give them protection, not only because they were rebels, but also through fear of displeasing their neighbour, the Massay. In this distressful situation, they have no other resource than to repair to the uncultivated parts round the Upas, and requested permission of the Emperor to settle there. Their request was granted, on condition of their fixing their abode not more than twelve or fourteen miles from the tree, in order not to deprive the inhabitants already settled there at a greater distance of their cultivated lands. With this they were obliged to comply: but the consequence was that in less than two months their number was reduced to about three hundred. The chiefs of those who remained returned to Massay, informed him of their losses, and intreated his pardon, which induced him to receive them again as subjects, thinking them sufficiently punished for their misconduct. I have seen and conversed with several of those who survived, soon after their return. They all had the appearance of persons tainted with an infectious disorder; they looked pale and weak, and from the account which they gave of the loss of their comrades, of the symptoms and circumstances which attended their dissolution, such as convulsions, and other signs of a violent death, I was fully convinced that they fell victims to the poison.

This violent effect of the poison, at so great a distance from the tree, certainly appears surprising, and almost incredible; and especially when we consider, that it is possible for delinquents who approach the tree, to return alive. My wonder, however, in a great measure, ceased, after I had made the following observations:

I have said before, that malefactors are instructed to go to the tree with the wind, and to return against the wind. When the wind continues to blow from the same quarter while the delinquent travels thirty, or six and thirty miles, if he be of a good constitution he certainly survived. But what proves the most destructive is, that there is no dependence on the wind in that part of the world for any length of time. There are no regular land winds; and the sea wind is no perceived there at all, the situation of the tree being at too great a distance and surrounded by high mountains and uncultivated forests. Besides, the wind there never blows a fresh regular gale, but is commonly merely a current of light, soft breezes, which pass through the different openings of the adjoining mountains. It is also frequently difficult to determine from what part of the globe the wind really comes, as it is divided by various obstructions in its passage, which easily change the direction of the wind, and often totally destroy its effects.

I, therefore, impute the distant effects of the poison, in a great measure, to the constant gentle winds in those parts, which have not power enough to disperse the poisonous particles. If high winds were more frequent and durable there, they would certainly weaken very much, and even destroy the obnoxious effluvia of the poison; but without them, the air remains infected and pregnant with these poisonous vapours.

I am the more convinced of this, as the worthy ecclesiastic assured me that a dead calm is always attended with the greatest danger, as there is a continual perspiration issuing from the tree, which is seen to rise and spread in the air, like the putrid steam of a marshy cavern.

EXPERIMENTS MADE WITH THE GUM OF THE UPAS-TREE.

IN the year 1776, in the month of February, I was present at the execution of thirteen of the Emperor's concubines, at Soura-Charta, who were convicted of infidelity to the Emperor's bed. It was in the forenoon, about eleven o'clock, when the fair criminals were led to an open space within the walls of the Emperor's palace. There the judge passed sentence upon them, by which they were doomed to suffer death by a lancet poisoned with Upas. After this, the Alcoran was presented to them, and they were, according to the law of their great prophet Mahomet, to acknowledge and to affirm by oath, that the charges brought against them, together with the sentence and their punishment, were fair and equitable. This they did, by laying their right hand upon the Alcoran, their left hands upon their breast, and their eyes lifted towards heaven; the Judge then held the Alcoran to their lips, and they kissed it.

These ceremonies over, the executioner proceeded on his business in the following manner:— Thirteen posts, each about five feet high, had been previously erected. To these the delinquents were fastened, and their breasts stripped naked. In this situation they remained for a short time in continual prayers, attended by several priests, until a signal was given by the judge to the executioner; on which the latter produced an instrument, much like the spring lancet used by farriers for bleeding horses. With this instrument, it being poisoned with the gum of the Upas, the unhappy wretches were lanced in their middle of their breasts, and the operation was performed upon them all in less than two minutes.

My astonishment was raised to the highest degree, when I beheld the sudden effects of that poison, for in about five minutes after they were lanced, they were taken with a tremor, attended with a subsultus tendinum, after which they died in the greatest agonies, crying out to God and Mahomet for mercy. In sixteen minutes by my watch, which I held in my hand, all the criminals were no more. Some hours after their death I observed their bodies full of livid spots, much like those of the Petechiæ, their faces swelled, their colour changed to a kind of blue, their eyes looked yellow, &c. &c.

About a fortnight after this, I had an opportunity of seeing such another execution at Samarang. Seven Malayans were executed there with the same instrument, and in the same manner, and I found the operation of the poison, and the spots in their bodies exactly the same.

These circumstances made me desirous to try an experiment with some animals, in order to be convinced of the real effects of this poison; and as I had then two young puppies, I thought them the fittest objects for my purpose. I accordingly procured with great difficulty some grains of Upas. I dissolved a half a grain of that gum in a small quantity of arrack, and dipped a lancet into it. With this poisoned instrument, I made an incision in the lower muscular part of the belly of one of the puppies. Three minutes after it received the wound, the animal began to cry out most piteously, and ran fast as possible from one corner of the room to the other. So it continued during six minutes, when all its strength being exhausted, it fell upon the ground, was taken with convulsions, and died in the eleventh minute. I repeated this experiment with two other puppies, with a cat and a fowl; and found the operation of the poison in all of them the same, none of these animals survived above thirteen minutes.

I thought it necessary to try also the effect of the poison given inwardly, which I did in the following manner. I dissolved a quarter of a grain of the gum in half an ounce of arrack, and made a dog of seven months old drink it. In seven minutes a reaching ensued, and I observed, at the same time, that the animal was delirious, as it ran up and down the room, fell on the ground, and tumbled about; then it rose again, cried out very loud, and in about half an hour after was seized with convulsions and died. I opened the body, and found the stomach very much inflamed, as the intestines were in some parts, but no so much as the stomach. There was a small quantity of coagulated blood in the stomach, but I could discover no orifice from which it could have issued, and, therefore, I supposed it to have been squeezed out of the lungs, by the animal's straining while it was vomiting.

From these experiments I have been convinced, that the gum of the Upas is the most dangerous and most violent of all vegetable poisons; and I am apt to believe that it greatly contributes to the unhealthiness of that island. Nor is this the only evil attending it, hundreds of natives of Java, as well as Europeans, are yearly destroyed and treacherously murdered by that poison, either internally or externally. Every man of quality and fashion has his dagger and other arms poisoned with it; and in times of war the Malayans poison the springs and other waters with it; by this treacherous practice, the Dutch suffered greatly during the last war, as it occasioned the loss of half their army. For this reason, they have ever since kept fish in the springs of which they drink the water; and centinels are placed near them, who inspect the waters every hour, to see whether the fish are alive. If they march with an army or body of troops into an enemy's country, they always carry live fish with them, which they throw into the water, some hours before they venture to drink it, by which means they have been able to prevent their total destruction.

This account, I flatter myself, will satisfy the curiosity of my readers, and the few facts which I have related will be considered as a certain proof of the existence of this pernicious tree, and its penetrating effects.

If it be asked why we have not yet any more satisfactory accounts of this tree, I can only answer, that the object of most travellers to that part of the world consists more in commercial pursuits than in the study of Natural History and the advancement of sciences. Besides, Java is so universally reputed an unhealthy island, that rich travellers seldom make any long stay in it, and others want money, and generally are too ignorant of the language to travel, in order to make inquiries. In future, those who visit this island will probably be induced to make it an object of their researches, and will furnish us with a fuller description of this tree.

I will, therefore, only add, that there exists also a fort of Cajoe-Upas on the coast of Macassar, the poison of which operates nearly in the same manner; but is not half so violent and malignant as that of Java, and of which I shall likewise giev a more circumstantial account in a description of that island.

J. N. FOERSCH.

[We shall be happy to communicate any authentic papers of Mr. Foersch to the public, through the channel of the London Magazine.]

Beschryving van den Vergif-Boom, Bohon-Upas, op het Eiland Java (Algemeene Vaderlandsche Letter-Oefeningen, 1784)

- Foersch, N. P. (1784), "Beschryving van den Vergif-Boom, Bohon-Upas, op het Eiland Java" (in Dutch), Algemeene Vaderlandsche Letter-Oefeningen (Amsterdam: A. van der Kroe en Yntema en Tieboel): 286-296, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015065144878&view=1up&seq=306 — "Description of the Poison Tree, Bohon-Upas, on the Island of Java"

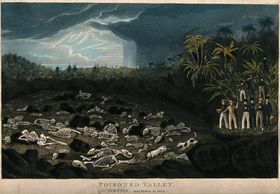

Départ et Arrivée du Criminel Condamné a Cueillir le Poison du Bohon Upas (stipple engravings, T. Rosalie after Monnet, 1785)

- Départ du criminel condamné a cueillir le poison du Bohon Upas, 1785, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1998-0426-23

Dans un Désert affreux d l'Ile de Java, croît le Bohon upas. Tout meurt; et nulle plante même ne végéte autour def cet abre. Les Criminels condamnés à la morte sont les seuls qui s'exposent a cueillir la Gomme ou le poison que son écorce distille. Un Prêtre Malais qui habite l'entrée du Désert, les instruit de la route, et des moyens qu'ils doivent prendre pour faire cette dangereuse récolte. La tête couverte d'un Bonnet de peau qui descend jusqu'à la poitrine, et auquel sont attachés des yeux de verre, les mains garnies aussi de gants de peau, ils ne partent qu'après avoir reçu les adieux de leurs parents qui pleurent sur leur mort presque certaine.

In a dreadful desert on the island of Java grows the Bohon upas. Everything dies; and no plant vegetates around this tree. Criminals condemned to death are the only ones who expose themselves, picking the gum or the poison that its bark distills. A Malay priest who lives at the entrance to the Desert instructs them on the route, and the means they must take to make this dangerous harvest. Their heads covered with a leather cap that goes down to the chest, and to which glass lenses are attached, their hands also covered with leather gloves, they do not leave until they have received the farewells of their parents, who weep over their almost certain death.

- Arrivée du criminel condamné a cueillir le poison du Bohon Upas, 1785, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1998-0426-24

Le Bohon upas entouré de cinq ou six arbres de son espece, croît sur un Sol brunatre tout couvert des débris de Cadavres. Le Criminel qui peut en approcher, en reçoit la Gomme dans une Boëte d'argent ou d'écaille. Ce poison est reçu avec transport par les Habitans de Java qui y trempent leurs armes, dont la moindre alleinte leur assure la mort de l'ennemi. Le Criminel assez heureux pour ne pas pírír dans ce voyage, est nourri le reste de ses jours aux dépens de l'Empereur; mais dans un e'space de trente années, de sept cents malheureux éxposés à ce danger, il n'en es revenu que vingt deux.

The Bohon upas, surrounded by five or six trees of its kind, grows on a brownish soil, covered all around with the remains of corpses. The Criminal who can approach it places the gum in a silver or tortoiseshell box. This poison is received from the carrier by the inhabitants of Java who dip their weapons [in it], the slightest amount allegedly assuring them of the death of their enemies. The Criminal fortunate enough to not perish on this journey is cared for the rest of his life at the expense of the Emperor; but, in a space of thirty years, of seven hundred unfortunate people exposed to this danger, only twenty-two came back.

Critical Responses

Antiaridae (Outlines of Botany, 1835)

- Burnett, Gilbert T. (1835), "(1621.) Antiaridae.", Outlines of Botany: Including a General History of the Vegetable Kingdom, London: John Churchill, p. 551-558, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044107230252&view=1up&seq=47

The celebrated Upas of Java, the Boom or Bohun Upas of the natives, is the Antiaris or Ipo toricaria of Leschenault and Persoon. The tree is named Antiar or Antschar by the Javanese, and the poison procured from it (as well as other deadly poisons, such as the Upas Tieuté, of which more here after,) is called Upas or Oupas in Java, and Ipo in Macassar, Borneo, and the neighbouring isles. Hence the first generic name is the one to be preferred. The history of the Upas affords a melancholy instance of the degree to which a love of the marvellous, and the passion for telling mysterious tales, by which a short-lived fame may be enjoyed, to be succeeded however by enduring con tempt, will mislead even well-educated men; for in the relation of Foërsch falsehood was so craftily blended with truth, that his story, although received at first with caution, was, from its very circumstantial details, for years esteemed, notwithstanding its wonderful character, as an authentic record. But, since bis many wilful misrepresentations have been detected, even those parts of the narration which are true, or based on truth, have been doubted, and the whole regarded as a cunningly devised fable. The researches of modern travellers of credit have, however, established the existence of the Upas-tree; and other very recent investigations have assured us of the reality of the Upas valley also. The collation of these two series of facts will put us in possession of the chief materials whence Foërsch composed bis tale, and expose the temptation by which be was seduced to declare that he had himself seen those things of many of which he had only heard, and which, marvellous enough as they are, the ignorance and superstition of the narrators had probably in the first place exaggerated, but which be seems to have conjoined for the sake of effect, and to have still further estranged from truth. The circumstances alluded to are in themselves most curious, and their coincidence in Java affords so strange an apparent corroboration, and at the same time so clear a refutation of Foërsch's romance, that it seems to gather from them an importance not properly its own[...]

The facts ascertained by different travellers, and confirmed on many hands, are the following. The Antiar or Bohun-Upas, is a native of Java and the neighbouring isles, growing to a large size, and being found not in barren districts, but in the most fertile places. So far from destroying other vegetables, climbing plants twist round its stem as they do round other trees; neither are its exhalations so noxious as to destroy birds flying over or animals that approach it; yet, although neither M. M. Deschamps and Leschenault experienced any inconvenience, other persons are said to suffer from headach, and to have uncomfortable sensations when in its vicinity, similar to those wbich are produced by the exhalations of the Munchineel tree, the Rhusradicans, and other plants, especially some of the Euphorbiacea. Leschenault even smeared some of the venomous juice over his hands with impunity, but he washed them immediately afterwards. The sap which exudes from wounds made in the tree is a bitter gum-resin. It is of a light hue when drawn from the young branches, and dark yellow if taken from the old stem, but both kinds become nearly black on drying. The Javanese make a mystery of its preparation, and pretend that the fresh sap is inert, and that it gains its power by certain additions they make to it, and the process it undergoes. But Hoosfield has shewn that these pretensions are false. In Java the poison is kept in a semi-fluid state, resembling treacle, while in Borneo it is rendered solid. It is usually preserved in the hollow joints of the bamboo, and, if excluded from the air, retains its extra ordinary powers for an unlimited time.

The natives use the Upas antiar, as well as the Upas tieuté, to poison their arrows, both those which are destined for war and the chase; and, before their conquest of Java, the Dutch suffered severely from wounds inflicted by these deadly weapons.

- Burnett observes a correspondence of Foersch's claim regarding the barren lands surrounding the Bohon Upas tree, and a later account by Alexander Loudon of an Upas Valley, or Guevo Upas, the Poison Valley, which appeared as "Extract of a Letter from Mr. Alexander Loudon to W. T. Money, Esq." in the Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London (v. 2, 1832), drawing a conclusion that:

"The origin of Foërsch's centaurian tale must now be evident: that Upas meant poison, and was an adjective term applied to deleterious things of various kinds, whether trees or places, he knew not; he had heard of the Upas, had probably witnessed its effects as a poison, and not improbably had seen the real Bohun Upas tree, which perhaps may sometimes grow in a barren district, such as he has described. He had heard of the Valley of Death, the Upas valley, and be might even have ridden round some sterile spot for thirty miles, fearing to tread upon its precincts, lest he should approach too closely to the chimera he had formed, by combining the accounts of the Upas valley and the Upas tree. As to the old priest, he might have heard from him the legend he relates; but for the numerous other facts used as embellishments to the tale, he must have been solely indebted for them to a fertile imagination."

Further Reading

- Sykes, W. H. (1837), "Remarks on the Origin of the Popular Belief in the Upas, or Poison Tree of Java", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (Cambridge University Press) (1): 194-199, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/25207492.pdf

- Gimlette, John D. (1923), Malay Poisons and Charm Cures (2nd ed.), London: J. & A. Churchill, p. 173-174, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015046341379&view=1up&seq=197

Few trees have been more amusing to the world than Arbor toxicaria, the ipoh or upas of Rumphius (“Herb. Amboin.," Vol. II., p. 263). The fables connected with it were first recorded in 1783 by Foersh, a Dutch doctor in the service of the Dutch East India Company. Criminals condemned to die, he wrote, were offered the chance of life if they would go to the upas tree and collect some of the poison, and of those who accepted the offer “only two out of twenty returned alive.” Those who were lucky enough to escape reported that “they found the ground under the trees covered with the bones of the dead.” “Not a tree,” he added, “nor blade of grass is to be found in the valley or surrounding mountains. Not a beast or bird, reptile or living thing, lives in the vicinity.” A putrid steam was supposed to rise from the tree[...] Charles Campbell very shortly refuted the “travellers' tales” of Foersh, and observed: “As to the tree itself I have sat under its shade, and seen birds alight upon its branches; and as to the story of grass not growing beneath it, everyone who has been in a forest must know that grass is not found in such situations." These facts were corroborated many years later by Vaughan Stevens and Ridley, who by personal experiments also proved that the juice of the tree can be applied to the unbroken skin and can be taken internally by the mouth without producing poisonous effects in human beings.

- Bastin, John (1985), "New Light on J. N. Foersch and the Celebrated Poison Tree of Java", Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 58 (2): 25-44, https://www.jstor.org/stable/41493016

in Literature

- In Canto III (verses 218-258) of "The Loves of Plants," the second part of Erasmus Darwin's 1791 poem The Botanic Garden, the UPAS, the HYDRA-TREE of death is described; in some print versions, the full text of the Foersch story is included as a supplement.

- William Blake's poem A Poison Tree (1794) from Songs of Experience, re: Stauffer, Andrew M. (Fall 2001), "Blake’s Poison Trees", Blake: An Illustrated Quarterly 35 (2), https://bq.blakearchive.org/35.2.stauffer

- In the Tenth Book of Robert Southey's 1801 poem Thalaba the Destroyer, the Upas Tree of Death is described, and Southey adds a footnote, crediting Darwin's work and suggesting an inspiration for Foersch's story of the poison tree may have originated with Hakluyt's account of Odoric of Pordenone.

- In Canto IV (CXXVI) of Lord Byron's 1812-18 poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage, the poison tree is as metaphor:

The harmony of things, -- this hard decree,

This uneradicable taint of sin,

This boundless upas, this all-blasting tree,

Whose root is earth, whose leaves and branches be

The skies which rain their plagues on men like dew --

Disease, death, bondage -- all the woes we see --

And worse, the woes we see not -- which throb through

The immedicable soul, with heart-aches ever new.