John Armstrong Chaloner

From Kook Science

| John Armstrong Chaloner | |

|---|---|

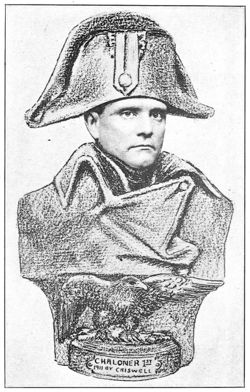

John Armstrong Chaloner in the style of a bust of Napoleon Bonaparte, from his book Robbery Under Law (1914) | |

| Born | John Armstrong Chanler 10 October 1862 Manhattan, New York |

| Died | 1 June 1935 (72) Charlottesville, Virginia |

| Alma mater | Columbia University (B.A., 1883; M.A., 1884) |

| Affiliations | Palmetto Press |

| Spouse(s) | Amélie Louise Rives (m.1888, dv. 1895) |

John Armstrong Chaloner (October 10, 1862 - June 1, 1935) was an American philanthropist, an heir of an Astor-related family (being a great-great grandson of John Jacob Astor), as well as a poet and author.

Chaloner was involuntarily committed by his family in 1897 to the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum at White Plains, New York, where he was held for nearly four years before he escaped, disappearing only to resurface and check himself in voluntarily to the Shaffer Sanitarium at Philadelphia, where he was found to be competent, after which he went to Virginia, where the courts agreed with the Pennsylvanian assessment. However, despite being free and considered sane in Pennsylvania and Virginia, his status under New York law meant his estate and inheritance continued to be held by his family in trust and doled to him as they saw fit, a case that he was forced to spend many years fighting in the courts. The cause of Chaloner's commitment had been over his claims to have developed what he termed the "X-Faculty," giving him certain mediumistic and psychical abilities — which he accessed by "graphic automatism" (automatic writing) and "vocal automatism", and through which he learned he was the reincarnation of Napoleon Bonaparte and received stock trading tips — and further claims of accompanying physiological changes, specifically that his facial features came to resemble Bonaparte's, and that his eye colour shifted from brown to grey.

Selected Bibliography

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1906), Four Years Behind the Bars of "Bloomingdale;": Or, The Bankruptcy of Law In New York, Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina: Palmetto Press, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008595118

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1906), The Lunacy Law of the World: Being That of Each of the Forty-Eight States and Territories of the United States, with an Examination Thereof and Leading Cases Thereon; Together with That of the Six Great Powers of Europe—Great Britain, France, Italy, Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Russia, Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://www.loc.gov/item/10027882/

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1907), Scorpio (Sonnets), Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://archive.org/details/scorpiosonnets00chaliala

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1911), The X-Faculty, or, the Pythagorean Triangle of Psychology, Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1912), Hell: Per a Spirit-Message Therefrom (Alleged): a Study in Graphic-Automatism, Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/000283648

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1912), Petition for the Impeachment for Malfeasance in Office of George C. Holt, Judge of the Federal District Court for the Southern District of New York, Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100618327

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1914), Robbery Under Law; Or, the Battle of the Millionaires: A Play in Three Acts and Three Scenes, Time, 1887; Treating of the Adventures of the Author of "Who's Looney Now?", Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://archive.org/details/robberyunderlaw00chal

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1914), The Swan-Song of "Who's Looney Now?", Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009793579

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1914), Pieces of Eight; a Sequence of Twenty Four War-Sonnets, Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://archive.org/details/piecesofeightseq00chal

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1915), "Saul"; A Tragedy in Three Acts, Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://archive.org/details/saultragedyinthr00chal

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1916), Jupiter Tonans: A Sequence of Seven Sonnets, Roanoke Rapids, N.C.: Palmetto Press, https://archive.org/details/jupitertonansseq00chal

- Chaloner, John Armstrong (1924), A Brief for the Defence of the Unequivocal Divinity of the Founder of Christianity as the Son of Jehovah, New York: Palmetto Press, https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008995305

Reading

Contemporary Reports

- Reller, Will W. (28 Nov. 1908), "Romantic Fight of John Armstrong Chaloner Against Relatives and New York Sanity Laws - Story of Man Who Seeks Custody of His Fortune and His Pursuits Along Psychological Lines Which Send Him to the Mad House. Can a Man Carry Red Hot Coals in Hand and Be Sane?", Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram: 8, https://newspapers.library.in.gov/cgi-bin/indiana?a=d&d=RPD19081129.1.8

Posthumous

- O'Connor, Harvey (1941), "The Amazing Chanlers", The Astors, New York: A. A. Knopf, p. 302-305

John Armstrong Chanler furnished the metropolitan press with a nine-day sensation when he “escaped" from Bloomingdale asylum on Thanksgiving Eve of 1900 by simply extending a usual walk. From time to time when a dead tramp was fished out of some suburban pond, the mystery of the missing Chanler was revived. He turned up voluntarily at a Philadelphia hospital, was checked out as sane, and resumed his solitary way of life at Merry Mills in Virginia, where he obtained from the court a certificate of sanity, backed by such eminent authorities as Dr. H. C. Wood of the University of Pennsylvania, Professor Joseph Jastrow of Wisconsin, president of the American Psychological Association, and William James of Harvard, who pronounced him sound of mind, but urged restraint in his psychological experiments.

At Bloomingdale this Chanler had acquired the gift of automatic writing, at first coarse, blasphemous stuff, which later turned into a Florentine romance of the time of Machiavelli (another Astor had also written, not automatically, of the licentious times of the Italian Renaissance). Poetry also was an art that came to him in Bloomingdale, and he turned out several hundred sonnets.

Brooding at Merry Mills with only a fierce parrot and a rose breasted cockatoo for companions, he resolved to rid himself of the name so disgraced by his brothers, and thenceforth signed himself Chaloner. “I have the temperament,” he wrote, “which makes it possible for me to stay angry for life.” He organized the Palmetto Press, that his anger might be heard, and wrote Four Years behind the Bars at ‘Bloomingdale, or The Bankruptcy Law in New York. “One may search fiction high and low for a case like this in real life,” commented the New York World. “It is one of the most remarkable stories of modern times. Here is a man of independent means, a man of affairs, a brilliant writer, an ardent sportsman and clever raconteur, sent to Bloomingdale, adjudged hopelessly insane, progressive, the physicians called his case.” Law journals praised the book as a stimulus to reform of the lunacy laws.

His anger flashed out in Scorpio No. 1, a quarterly bound in purple with a seven-tailed whip in gold and red, the title page adorned with a quotation from Tacitus: “Keenest is the hatred of kin.” Scorpio aimed “at the strength of Juvenal, the keenness of Voltaire, the fierceness of Swift, and the form of Byron.” Chaloner had material enough on the “dishonesty, hypocrisy and crimes of the Rich" to run Scorpio for years. Of his brothers and sisters he wrote:

Yet these lovely ladies left me to dry-rot,

Linger and perish in a noisome cell;

And yet these warlike brothers blood forgot

And doomed me untried to a living Hell!

Three ladies and four gentlemen's the roll,

Their record's knell do I now sternly toll.His estate was now in charge of a “committee.” Having tried in vain to get his allowance raised from $17,000 to $32,000 a year, in revenge he published his will, giving all to charity. That may well have impressed his brothers as another proof of insanity. He needed the money, he said, to advertise Scorpio, without which it could never reach the attention of the public. “Your petitioner,” he pleaded, “would greatly like to cultivate his newly discovered talent of shooting folly as it flies, in correctly built sonnets.”

In 1913 he took a town house in Richmond and discovered that rich hell-hounds were taking the daughters of the poor out joyriding, wrote more sonnets against New Yorkers unable to pronounce “r,” against the split skirt and the brutality used on English suffragettes, and a canto addressed to the cockroaches at Bloomingdale which defended him against the bedbugs. It was about this time that in a trance he received a message from Thomas Jefferson Miller, a late Confederate officer, who described Satan as resembling Napoleon and ruling in a throne room made of rubies the size of bricks, mortared by diamonds. The frontispiece of his latest book showed Chaloner under a Napoleonic hat.

By 1915 the famous character who was sane in Virginia and insane in New York was shown in court to have an estate of $1,473,000, with an income of $89,000, of which he was allowed $24,000. The newspapers reported that he had abandoned his carriage, in which he used to drive with a shotgun over his knees to use on motorists who scared his horse, for a “jitney." He had published a play, Robbery under the Law, or The Battle of the Millionaires, and The Hazard of the Die, and promised a “chain of plays that equals Shakespeare's length.” In his Hell and the Infernal Comedy he explained that he still rejected spiritualism, but believed in necromancy as practised by “my fair predecessor, the Witch of Endor.”

Trained for the law, Chaloner was often in the courts. In 1908 Town Topics linked his name with his former wife, Amélie Rives, now Countess Pierre Troubetskoy, and was promptly sued for libel.

In March 1909 Chaloner shot and killed John Gillard, whose wife had fled to Merry Mills for protection from his drunken rage. He was never arrested, as the case was held to be justifiable homicide, exercised, as Chaloner put it, by one “practicing Christianity . . . in these weak-kneed chocolate-eclair spined times.” The New York Evening Post, during the Harry K. Thaw episode, ran a paragraph saying: “The latest prominent assassin had the rare foresight to have himself declared in sane before he shot his man.” Chaloner sued and got $17,500. The Washington Post carried a purely factual story of the shooting; Chaloner sued and was upheld with a one-cent award.

Time and again the man who was still insane in New York tried to get himself adjudged sane. Joseph H. Choate, attorney for his “committee,” declared his only sign of sanity was engaging a lawyer. In his own defence Chaloner could cite a letter he had published in the New York Herald of August 6, 1914, predicting that the war would last three years, that the German fleet would be sunk or captured, that permanent peace would ensue with Hungary independent and Serbia greatly enlarged. In 1919 he won the long fight for judicial confirmation of his sanity and returned to New York, an aging man of fifty-seven. He wandered about friendless, delivered a lecture at Christ Church on his “X-faculty,” and revealed “the secret which has heretofore baffled humanity — the mystery of the mind of mankind.” It turned out to be Confucius' Golden Rule. In the winter of 1920-1 he gave free lectures at the Cort Theatre, attended by few, and in 1924 published a defence of religious fundamentalism dedicated to Bishop Manning.

But he preferred the solitude of Merry Mills, where his servants all departed the house at sundown to let him wrestle alone with the spirits of darkness, protected only by his dogs. There he died, a lonely, embittered old man.

- Lucey, Donna M. (2006), Archie and Amélie: Love and Madness in the Gilded Age, New York: Harmony Books